A downloadable PDF version of this article is available here.

The ability to access social interactions is important for everyone, but many people may often be denied access or experience reduced access because of physical, cognitive, or social barriers. A lack of quality access leads to impoverished social experiences and a host of other problems such as loneliness, depression, and anxiety. My research agenda aims to understand how we can design and develop technology to support social interactions – exploring how sociality crosses into both physical and virtual spaces. For physical environments, I have designed and developed assistive technology as a therapeutic tool using whole-body interactive systems to expand modes of communication. Beyond physical spaces, my dissertation focuses on social interactions within and across social media platforms, including a Minecraft virtual world for children with autism, through ethnographic methods. In my future research, I will explore how individuals navigate access not only from platform to platform, but also from the physical world to the virtual and back again. Insight from this work will lead to theoretical and practical contributions of how individuals with disabilities and their social networks adopt, use, and modify technical systems that facilitate social interactions. Further, my work will lead to a better understanding of these communities and how to design more inclusive technology.

Assistive Technology for Children with Autism

Whole-Body Interactive Systems

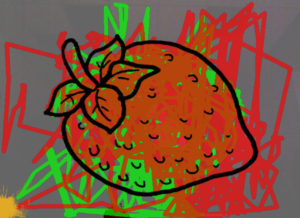

Figure A. Strawberry outline colored by the user.

Figure B. A target with the silhouette of the user in the background.

Access to otherwise prohibitively expensive (e.g., money, time, energy) therapy is made possible by using whole-body interactive technology and augmenting the therapeutic and home environments for users. I conducted research of two systems using whole-body interactions – SensoryPaint and DanceCraft – which augmented therapies already being employed by children with autism. Both systems were developed using the Kinect, an inexpensive device that can be placed in a user’s home or doctor’s office. These projects allow for a more inclusive therapeutic environment by creating accessible, inexpensive solutions.

SensoryPaint uses a projection on a wall that the users interacted with using rubber balls. The user receives visual feedback of their activity via a silhouette displayed on the projection. The system allows for multiple types of interaction. For example, the user can digitally “paint” with the Kinect, tracking the ball and displaying the ball’s path in various colors on the wall (See Figure A). The user can also throw the ball at the projection to get a “splash” effect (See Figure B). From the results of the pilot study of SensoryPaint, I found that whole-body interactions can be more engaging for children than traditional therapies by giving participants different interactive options that suit their specific sensory needs. Including a flexible interface allows both therapists and children to use relevant segments of the program and change settings as needed. I presented these results at the Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing (UbiComp) where I was nominated for a Best Paper award [8].

Figure C. Shadow puppet interface of DanceCraft.

Following the SensoryPaint study, I led a team of undergraduates to design and develop the DanceCraft system. The interface uses a similar silhouette feature that gives the user visual feedback on their activity. The user follows along with pre-recorded dances displayed as a “paper doll” figure (See Figure C). By including a feature to replay recorded dances on-the-fly, therapists and instructors can record dances specific for each child and session. The replay feature also allows for children to watch their own dance choreographies, giving them instant feedback. A therapist can then track a child’s progress across sessions through their saved recordings. Future iterations of the DanceCraft software will calculate whether the user’s captured dance moves are the correct dance moves as prescribed by the therapist. A pilot study of DanceCraft showed the feasibility of augmenting therapy in the home. I coauthored these preliminary findings, which were presented at the ACM Tapia Diversity conference [1], and a manuscript for the Transactions of Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) journal is currently in progress. Future work on these whole-body interactive systems will focus on creating intelligent software that can adapt to a growing, developing child’s needs and be intuitive for parents and therapists.

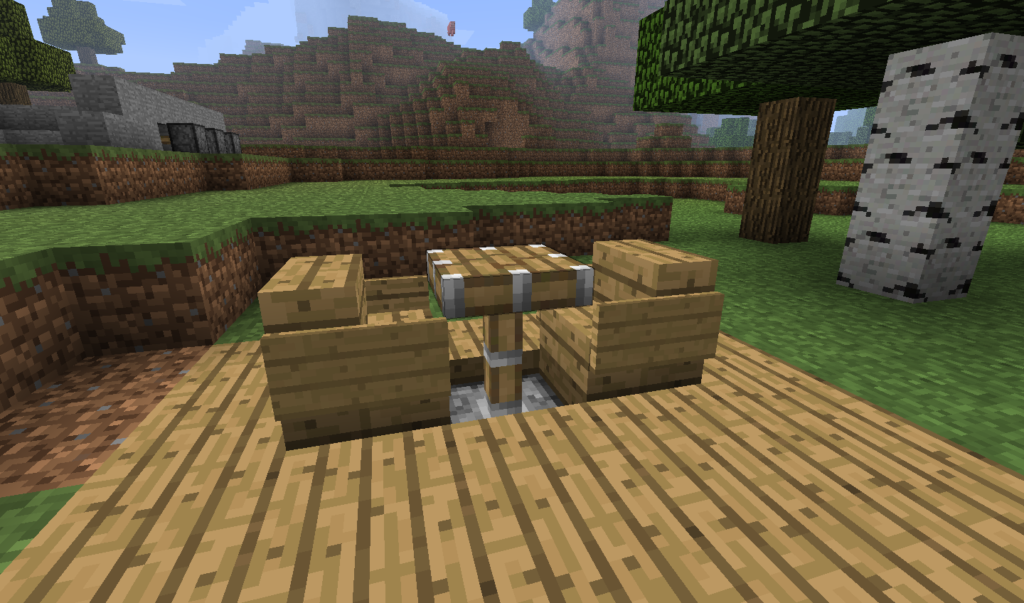

3D Printing from User-created Models in the Minecraft Virtual World

Minecraft is a popular virtual “sandbox” – with currently over 27 million units of the software sold – where players can build and create objects, environments, and worlds with a high degree of freedom. The multiplayer-capabilities of virtual worlds in Minecraft make it an ideal system for examining how technology facilitates and drives social interactions between users. I designed and programmed software that allows players to 3D print models of objects they have created within Minecraft. The application takes the coordinates of an object and translates it into a file that can be sent to a 3D printer, making their creations come to life in a sense. I designed the software to leverage the familiar interface by creating it as an add-on for Minecraft. To use the program, the user creates the 3D printing “magic wand” object within the virtual world, types in commands for the wand in the Minecraft interface, and then saves the files to the local computer. This program has potential in establishing engaging social interactions with greater accessibility due to the inherent nature of virtual environments, where conditions such as geographical or physical limitations are less hindering. Future work in this project will explore how users experience blending virtual creation of 3D objects with their tangible, physical representations. As part of a campus-wide effort to retain underrepresented students in STEM, this work was presented by my undergraduate mentee at the UCI Summer Research Symposium [9].

Exploring Virtual Worlds as a Support for Social Play in Children with Disabilities

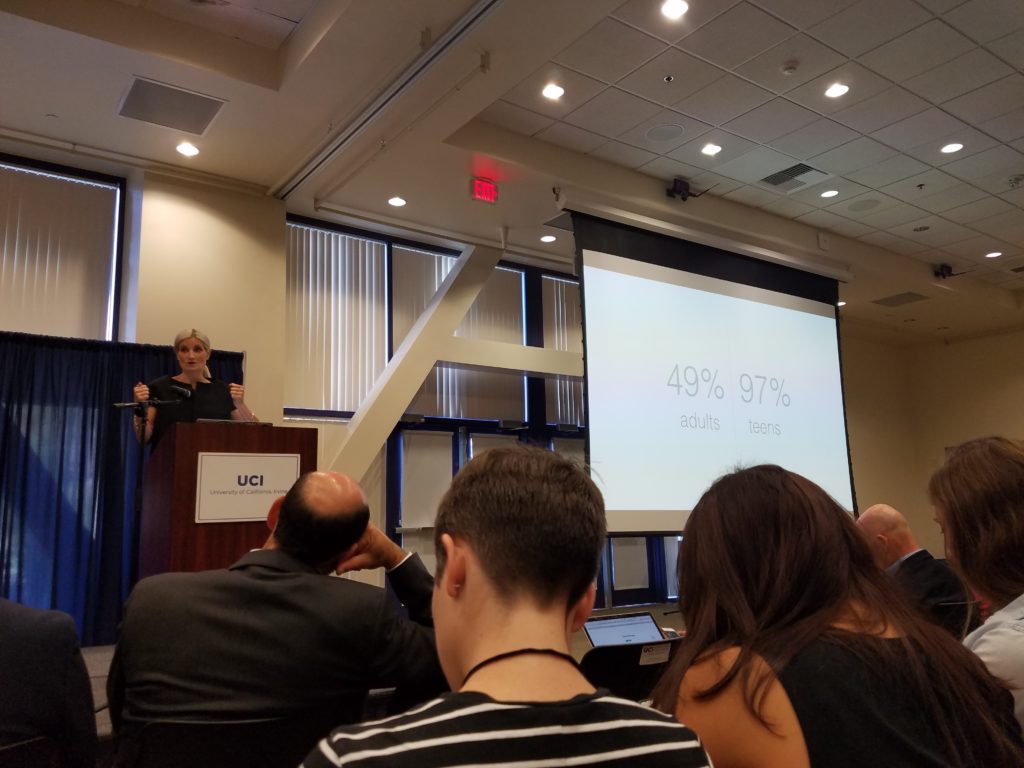

Autcraft is a specific iteration of a Minecraft virtual world dedicated to children with autism and their allies. Drawing from work in Disability Studies, my dissertation examines data collected from ethnographic research conducted over three years in Autcraft (See Figure D). My research has uncovered how the Autcraft community works to create a safe, inclusive space through both social and technical means [6]. Parents actively work to maintain safety and accessibility in the Autcraft community through modifying Minecraft and other mainstream technology to create assistive devices [5]. Additionally, the findings from this work indicate the importance of a supportive communication framework (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Twitch) that has emerged in the Autcraft community [7]. This constellation of social media is comprised of different platforms used in tandem to create a social, community experience. Community members can thereby empower themselves through online activism that supports better treatment of individuals with disability [2]. This also gives the children an outlet to express themselves creatively on safe online platforms [4]. Ultimately, I found the community searches for, practices, and defines sociality through the various communication channels and means of communication indicating evolving definitions of what it means to be social [3,7]. Results from this research project have appeared in multiple venues, including Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI) and Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (CSCW).

Figure D. A screen shot of my avatar, ResearcherKate – used to complete my virtual world ethnography.

Contributions of Dissertation

My dissertation contributes an empirical understanding of how access is granted to some individuals and not to others, creating an uneven distribution of experiences when interacting with technologies. This includes an exploration of how the intersectionality of multiple identities of community members, such as autistic or child, impacts social play online and how social play enables the performance of these identities. Insight from my work can help shape our scholarly understanding of how users approach technology, as well as some of the work marginalized users do to fully experience interactions. This includes some of the “Do-It-Yourself” activities individuals engage in to make systems more usable for themselves and their communities.

In this work, I highlight the value of virtual social interactions for marginalized users. When scholars, designers, therapists, or parents privilege physical, face-to-face social interactions over virtual ones, they run the risk of making invisible those who prefer, or have better access to, virtual social interactions. My dissertation challenges the mainstream discourse and contributes to normalizing social play as it occurs in virtual spaces for children with autism. Often, society tells these children they should focus solely on their physical-world engagements, while their online relationships and experiences are discounted. Children with autism are just one example of a subset of people who may prefer virtual interactions.

Finally, my work contributes a new way for HCI researchers to define and study social media. This work expands the definition of social media to include games and virtual worlds, beyond the scope of other social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr. The ethnographic methods used in this project also exemplify how HCI researchers should look beyond the bounds of a single social platform to understand a user or a community of users. Social media platforms work together to create an organic network for social interaction. This holistic lens of research allows for a far more complete understanding of users, which is necessary to create access and inclusion.

Research Agenda

My future research program will continue to explore the frontier where physical and virtual interactions no longer simply coexist, but are seamless. My work will encompass the following three themes: 1) understanding how people use a constellation of social platforms, 2) understanding disabled embodied experiences as mediated by technology, and 3) using the lens of intersectionality to represent a more complete person regardless of ability. To explore these threads, my research lab will engage in community-based work with individuals with disability and relevant organizations. Together we will answer questions regarding how we can design and develop sustainable technology that mediates social interactions and how access to these social interactions will improve quality of life. Research activities will include: designing and developing software for virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) platforms in tandem with whole-body sensors; holding workshops with marginalized individuals to both help with the design of these systems and to test the efficacy of the systems; and outreach programs with students in the department with local groups and schools.

This research will not only further the field in terms of understanding how people can build innovative technology, but also aid in the academic STEM pipeline for underrepresented students. As with my previous work, I will continue to mentor graduate and undergraduate students who are interested in working with marginalized populations in the areas of technology, games, and media studies. Results from this work will be published in conferences and journals geared towards HCI (such as CHI, Ubicomp, and ASSETS). My goal is to produce scientific results from multiple, diverse perspectives that will ensure a broader impact.

References

[1] J.K. Brown, K.E. Ringland, and G.R. Hayes. 2016. DanceCraft: A Whole-Body Dance Software for Children with Autism. Tapia Celebration of Diversity in Computing 2016.

[2] K.E. Ringland. 2017. On Being “Autsome”: An Exploration of Online Social Play as a Means of Empowering Autistic Youth. Popular Culture Association / American Culture Association.

[3] K.E. Ringland. 2017. Minecraft as a Site of Sociality for Autistic Youth. QGCon 2017.

[4] K.E. Ringland, L.E. Boyd, H. Faucett, A.L.L. Cullen, and Gillian R. Hayes. 2017. Making in Minecraft: A Means of Self-Expression for Youth with Autism. In Proc. IDC 2017, ACM.

[5] K.E. Ringland, C.T. Wolf, L.E. Boyd, M. Baldwin, and G.R. Hayes. 2016. Would You Be Mine: Appropriating Minecraft as an Assistive Technology for Youth with Autism. In Proc. ASSETS 2016, ACM.

[6] K.E. Ringland, C.T. Wolf, L. Dombrowski, and G.R. Hayes. 2015. Making “Safe”: Community-Centered Practices in a Virtual World Dedicated to Children with Autism. In Proc. CSCW 2015, ACM.

[7] K.E. Ringland, C.T. Wolf, H. Faucett, L. Dombrowski, and G.R. Hayes. 2016. “Will I always be not social?”: Re-Conceptualizing Sociality in the Context of a Minecraft Community for Autism. In Proc. CHI 2016.

[8] K.E. Ringland, R. Zalapa, M. Neal, L. Escobedo, M. Tentori, and G.R. Hayes. 2014. SensoryPaint: A Multimodal Sensory Intervention for Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. In Proc. UbiComp, ACM.

[9] Tamimi, A., Ringland, K.E., Hayes, G.R. 2016. “Developing a User-Friendly System to 3D Print Minecraft Creations.” UCI Summer Research Colloquium. Irvine, CA.

Acknowledgements: We thank the members of Autcraft for the warm welcome into their community. We also thank members of LUCI and the anonymous reviewers for their feedback on this paper, and Robert and Barbara Kleist for their support. This work is covered by human subjects protocol #2014-1079 at the University of California, Irvine.

Acknowledgements: We thank the members of Autcraft for the warm welcome into their community. We also thank members of LUCI and the anonymous reviewers for their feedback on this paper, and Robert and Barbara Kleist for their support. This work is covered by human subjects protocol #2014-1079 at the University of California, Irvine.