Check out the episode through your favorite listening platform here: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/podcastbyarmy/episodes/Podcast-by-ARMY-Ep-2-Happy-Birthday-our-baby-star-candy–golden-maknae–Jungkook–and-Weverse-sucks-e28oa8t

Tag: ARMY (Page 2 of 2)

Understanding the Collaborative Construction of Playful Places in Online Communities

By: Kathryn E. Ringland, Arpita Bhattacharya, Kevin Weatherwax, Tessa Eagle, and Christine T. Wolf

[This article was written by Kate with the help and support of her co-authors.]

This work is cross-posted on Medium: https://kateringland.medium.com/armys-magic-shop-668cb8a3c0c0

Preview: Using ethnographic fieldwork, we dive into the world of BTS and ARMY’s Magic Shop. The Magic Shop is a conceptual place for community members to relax, connect, and support one another. The Magic Shop is built on a foundation of play and exists in all the spaces that the BTS ARMY community lives and plays. This research helps us understand the deep importance of the BTS ARMY Magic Shop to community members and how we can create better and safer platforms for the community in the future.

This work will be appearing at CHI 2022. The preprint can be found at https://bit.ly/MagicShopCHI2022

Introduction

When we think about researching play, we often think of studying play in children, designing educational games, or using games to improve health. In this work, we’ve taken research on play in an understudied direction by looking at adults engaging in play for their leisure or as a hobby. In particular, we are looking at spaces not intentionally designed for play — that is, technologically mediated social spaces that are repurposed as socially playful places. For example, we are looking at social media platforms instead of multiplayer games where the play is scaffolded into the platform. This research is vital for better understanding how communities at play use technology. Outcomes of this work will ultimately help designers and researchers build better supportive and safer platforms for communities in the future.

Specifically, we turned our attention to the musicians BTS and their fandom, ARMY. We look at ARMY because of the community’s reach and diversity. Composed of a diverse but often underrepresented majority, ARMY is also a largely misunderstood community as it experiences biases, stereotyping, and oppressions that intersect across the different identities and interests of people in this fandom. We hope this work helps to reverse some of the stigma around ARMY and fandoms as a whole.

The goal of this work is to illustrate how BTS and ARMY work together to create a socially playful place in-person and online, built upon what the artists and community members call the “Magic Shop.” The foundations of this Magic Shop are people and their shared values, transcending the physical space to online and emotional or abstract places.

BTS & ARMY

BTS (방탄소년단 or Bangtan Soyeondan) is a group of seven musicians from South Korea who debuted in 2013. Their fandom, ARMY, has been growing globally since the band’s inception. ARMY, as a community, uses a variety of social media platforms to communicate such as Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, and Weverse. ARMY has a flat, non-hierarchical and participatory power structure [6]. That is, there is no clear “leader” of ARMY, other than, perhaps, the BTS members who also consistently share their power and success with ARMY.

ARMY has been stigmatized in the media for a number of reasons, including its majority fem-identifying membership and its supposed “bot-like” behavior [7]. However, as this work and others have shown, this is far from reality. ARMY is a large, diverse fandom with many different contexts, experiences, and values, and cannot be described in singularity [1]. ARMY is perhaps best known for their organizing and activism, such as raising donations for causes like Black Lives Matter in short periods of time.

Welcome to the Magic Shop: Research Methods

In this study, we report the findings from an ongoing online ethnographic study of the ARMY community. Data were collected through ARMY’s public social media posts on Twitter and TikTok, as well as through publicly available media posted by BTS on social media platforms including TikTok, Twitter, Weverse, YouTube, and VLIVE (this portion of the study was conducted before the members of BTS opened their individual Instagram accounts in December 2021).

I was responsible for all data collection and primary data analysis, identifies as an ARMY and has been on ARMY TikTok since September 2020 and ARMY Twitter since January 2021. For more details about data collection and analysis, please refer to the full paper.

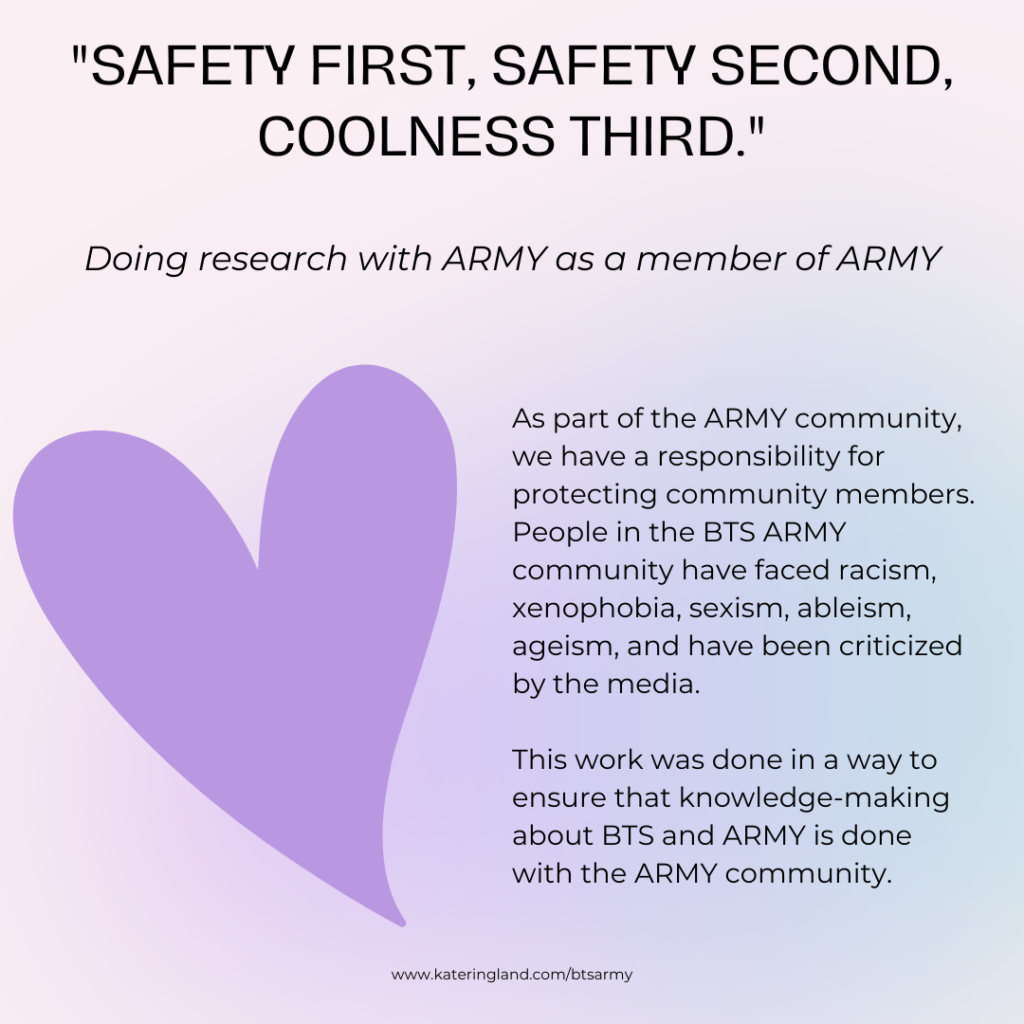

Important Research Considerations: Keeping BTS & ARMY Safe

Safety of BTS and ARMY are the priority in conducting this research. This work is exempt from ethics board approval because it involves ethnographic observations of public social media data. However, I and my co-authors took extra care while collecting, analyzing, and presenting this data.

As a member of the ARMY community, I take responsibility for protecting individuals who may interact with my various social media accounts. The BTS ARMY community has a history of being marginalized, including incidents of racism, xenophobia, and ageism. Further BTS ARMY faces more criticism among media and other outsiders [2,4,5]. ARMY has a fraught history of outsiders seeking to cause harm or use ARMY and BTS for their own profit or agenda [8,9].

The epistemic violence [11] enacted upon the community has left many with little trust for academia, with valid cause. For this reason, being a member researcher was imperative for this work to be positively received by the community and to ensure that knowledge-making about BTS and ARMY is done in conjunction with the ARMY community. At the same time, to ensure validity for research contexts in addition to the ARMY fandom and that solely my perspectives are not biasing this research, I worked with other ARMY and non-ARMY co authors during the analysis and writing process.

The data presented in these findings are exemplary of the themes found during analysis while prioritizing the integrity of the community. Everything has been anonymized and paraphrased unless otherwise noted.

This work relies on data from my online ARMY community where I am transparent about my identity as a researcher/professor and an ARMY. Therefore, when ARMY is referred to in the study, this is referring specifically to my extended ARMY community, rather than ARMY as a whole. It serves as a starting point for scholars to understand the ARMY community and playful adult places more broadly.

BTS & ARMY Creating the Magic Shop Together

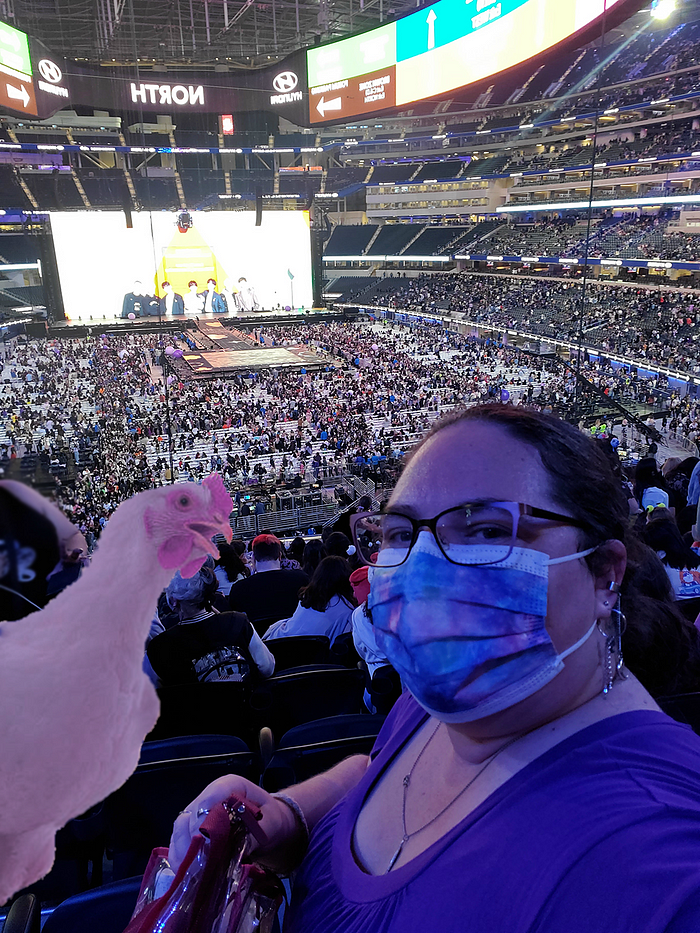

The Magic Shop exists in the spaces where ARMY and BTS go to seek comfort and to play with one another. The Magic Shop can exist anywhere BTS and ARMY have the potential to play, such as in online spaces (social media) or in offline spaces (concert venues). To create the Magic Shop, BTS engages in and encourages playful activities through their conversations and content. ARMY then follow suit in fostering play through fan-made edits and commentary, role-playing, and in-group humor. BTS and ARMY engage in play to construct safe and enjoyable online community places.

The play of BTS and ARMY in the Magic Shop should not be dismissed as less valuable than other aspects of life because it is play among adults or a hobby or leisure activity. Indeed, BTS and ARMY’s play has real-world impact and consequences — not the least of which is to support coping, meaning-making, and a sense of connectedness, thus improving quality of life and well-being for those in the community [3]. “Play” as we understand it, is a concept big enough to be a thing that is both purposeful and joyfully purposeless. This work provokes the need for future research taking a more expansive view of play — and a more expansive view of its benefits and boundaries in the everyday lives of communities online.

Some of ARMY’s play includes content transformation and curation, creating specific themed accounts, humor, crafting theory about BTS content, and creating new content. Doing these activities builds upon the foundation of the playful place set by BTS. For example, the following video is a skit performed by BTS on the Late Late Show with James Corden.

From this type of content, ARMY then create various content including hourly or daily accounts of specific clips that ARMY use to convey a mood or to add to conversations playfully.

The Magic Shop in online spaces has become all the more meaningful since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic when BTS, due to public health concerns, canceled their world tour and ceased all in-person activities with fans. Both ARMY and BTS leaned into the spaces still available to them — that is, online social media platforms — to continue creating this sense of community and connectedness. ARMY may not know each other’s legal names or even reside in the same country, but they have nevertheless created an intimate bond through play as well as connection to BTS, their message, and their discography. BTS and ARMY, first and foremost, are connected to one another by BTS’s music. This is the first point of contact and the common ‘language’ used throughout the community. Other media and platforms, then, become further means of communication.

Boundaries of Play in and out of the Magic Shop

Being able to play together requires a feeling of safety (whether they are actually safe or not) and trust between players [10]. Likewise, the Magic Shop cannot exist without these prerequisites. Many of these playful moments only have meaning within the playful place. Outside the playful place, much of the antics and humor can be misunderstood and stigmatized. Concerns about this can be seen in how ARMY negotiate with one another about what is appropriate “for the timeline” (that is, public posts) and what should be reserved for private conversation. Indeed, this is reflected in the careful choosing of examples for this paper, as well as the extensive explanation of the methods in this work. For the play to be truly playful, a trust between members of the community must be developed to create the sense of consent and safety needed for fun play.

In fact, when the Magic Shop is noticed by outsiders (such as a reporter taking ARMY tweets out of context and without consent), there is a sense of violation among ARMY — play no longer feels playful. Almost all of ARMY’s playful activities occur on public platforms and can be accessed by outsiders at any time, yet the community maintains a sense of in-group and out-group engagement. ARMY still holds to the trust among each other and in BTS as they go about their play. This type of social clustering within a public space without any physical or digital boundaries is often seen in interest groups (such as, gaming, other fandoms) and is also facilitated by the current tailoring algorithms on social media.

The time and place to be playful is context-dependent — both the context inside and outside of the Magic Shop. The public nature of these platforms requires extra social effort and infrastructure to maintain the boundaries of the community’s playful place. Within ARMY spaces, the community has leveraged affordances of the various social media platforms at their disposal (such as using the report and block feature, embedded videos and gifs, threads on Twitter, music on TikTok), as well as social norms for this boundary maintenance. Without having a strict “game” platform, BTS and ARMY have still managed to foster a set of rules for their play. This includes following BTS’s lead in knowing what is meant to be fodder for playful content and what is not (such as being respectful of emotionally laden images and video).

Outro

The goals of this study were (1) better understand how communities at play use technological platforms for play even when they are not designed as such and (2) to begin to reverse the stigma and marginalization of BTS and ARMY. BTS and ARMY have built a community based on mutual respect, love of music, and being playful with one another in their Magic Shop. The Magic Shop is often impacted by real world non-play issues such as being summarily dismissed, harassed, and stigmatized by outsiders, which can harm BTS and ARMY. The members of the community collectively work to look out for each other’s well-being and reorient to restore play in the Magic Shop — making sure that BTS and ARMY are safe and having fun.

Curious to learn more about this research? Visit: https://kateringland.com/btsarmy

💜 Thank you to those who provided invaluable feedback on drafts of this work including Breanna Baltaxe-Admony, Kendra Shu, and Severn Ringland, as well as our anonymous reviewers. This work was funded in part by the University of California President’s Office. A very special thank you to the ARMY community and those within the ARMY community that have helped shape this work. Finally, thank you to BTS for their music and continued love and support of the ARMY community. 💜

A video of the presentation of this work can be found here

References

3. Jin Ha Lee, Arpita Bhattacharya, Ria Antony, Nicole Santero, and Anh Le. 2021. “Finding Home”: Understanding How Music Supports Listerners’ Mental Health Through a Case Study of BTS. In Proc. of the 22nd Int. Society for Music Information Retrieval Conf., 8.

6. So Yeon Park, Nicole Santero, Blair Kaneshiro, and Jin Ha Lee. 2021. Armed in ARMY: A Case Study of How BTS Fans Successfully Collaborated to #MatchAMillion for Black Lives Matter. CHI 2021: 14.

10. Jaakko Stenros. 2014. In Defence of a Magic Circle: The Social, Mental and Cultural Boundaries of Play. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association 1, 2: 39. https://doi.org/10.26503/todigra.v1i2.10

11. Anon Ymous, Katta Spiel, Os Keyes, Rua M. Williams, Judith Good, Eva Hornecker, and Cynthia L. Bennett. 2020. “I am just terrified of my future”: Epistemic Violence in Disability Related Technology Research. In Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Extended Abstracts (CHI ’20), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1145/3334480.3381828

This is a summary of the work presented at SCMS 2022. This is cross-posted on Medium: https://medium.com/p/d8ebbe436fa2

Play happens everywhere and is a universal human experience. However, questions of accessibility still challenge many playful spaces. As diverse as people are, there are a diverse set of needs in order to access an activity, interaction, or experience. We find, though, that disabled individuals are often not accommodated in playful places.

I turn particularly to online playful spaces where some disabled people may find the primary source of their interactions. These online spaces become community places, where people with like-interests congregate, form relationships, and have fun. For playful communities, creating access means both grappling with platform design, including appropriation and modification of technology, and iterating on community norms and expectations to accommodate community members.

In this presentation, using data from ethnographies from two different playful communities, I will explore how the platform and community values are entangled and impact not only the playfulness, but also the accessibility of the space [3,6].

Methods

For both the case studies used in this work, I used ethnographic methods where I was embedded as a participant observer in the community for an extended period of time. In each community, I collected data from my own observations, public social media content, and community produced content. This work is qualitative and while I use some mixed methods, such as surveys, I mostly use that to triangulate what I am already finding in my qualitative work. This means that this work goes very deep into some community spaces and narrows in on specific aspects of my work. In order to preserve the safety of the community members, everything is paraphrased, abstracted, or anonymized as appropriate.

I identify as disabled scholar and activist, which means I approach most of my research with a critical disability lens. I look at spaces through a lens of deconstructing ableism that is occurring there, as well as trying to better understand communities from the perspective of making members feel safe, included, and cared for.

Autcraft

The first ethnography was conducted in a community centered around the video game Minecraft — Autcraft — was founded to create a safe space for autistic youth [5]. The Autcraft community uses various methods including modifying game software, leveraging other social media platforms, and adhering to a strict code of conduct for members to address not only the needs of autistic youth, but to accommodate other access needs [3].

The Autcraft community uses a variety of technological platforms in their community, but it is centered around the video game Minecraft. They use plug-ins and modifications to the software in order to make the game more accessible for the players. There are many different ways the community creates “access” through technological means and many of these technological implementations have been iterated on over time.

The majority of communication in the game world happens via text or through avatar interactions, which are quite simplified compared to some other multiplayer games. This was another intentional choice by the community. If the text in the image above were happening live, it could be moving up the screen fairly quickly. While this is still preferred to other modes of communication, it has its challenges and takes some getting used to.

After learning of a player in the community who was losing their vision, they added a new plug-in to the game in order to make the text chat more accessible. Now the different lines are separated by a symbol of the players choice, such as the dash. Specific titles and the player’s name is also highlighted in different colors. In making this change, the community ended up making text chat more accessible for many of the players.

The reason many people join the Autcraft community is because they had difficulty fitting in, finding friends, or, more broadly speaking, getting access to the play in a Minecraft space. Therefore, for many on Autcraft, being helpful and supportive is one of the most important parts of their sociality. The community has found it important enough to write into their rules and actively encourages this behavior through rewards, such as special titles such as member of the week.

Community describe hanging out with their friends on the Autcraft community much in the same way other youth online have. They spend time with their Autcraft friends online by interacting through forums, instant messaging, and “hanging out” in the Autcraft virtual world. And although not typically physically collocated, these youth on Autcraft consider these relationships to be meaningful friendships.

BTS’s ARMY

The second, ongoing ethnography is being conducted within the ARMY community, the fandom for the Korean musicians, BTS [4]. Much like the Autcraft community, the ARMY community is global. Unlike the Autcraft community, ARMY is a community made of loose-ties and more porous boundaries for community membership [2]. Therefore, how the community engages in play and accommodates access needs of members is notably different from the Autcraft community, as there are no central individuals making decisions about accommodations.

Additionally, because ARMY tends to use public social media platforms, the amount of control they have over the technology is very different from Autcraft. One way the community creates access is by smaller sub-communities using whatever platforms work for them. Smaller groups of ARMY, then, might be found on a modified Discord server or in a group chat. BTS, and the band’s use of various social media platforms, might also dictate what platforms are the most popular among ARMY.

More often, the social infrastructure is altered and iterated upon in order to create access. Specialized accounts to create spaces for disabled or Deaf — or any other subgroup — exist to help foster support and push for more access. For example, as a disabled ARMY, I have been pushing for more alt text to be incorporated in community members’ posts on social media. This also means asking the social media platforms to create more access for users as well.

This sort of activity is important because much of ARMY’s play are fan edits, parody accounts, threads of music and videos, art, and commentary about BTS. In fact, ARMY and BTS often play together, each creating content, communicating via various social media platforms, and share the same goals. The play is very referential, often including layers of inside jokes. For example, there is a plethora of content that explicitly references BTS’s known love for chicken [1].

Like the Autcraft community, ARMY are mindful of social justice issues, especially with regard to access. In both communities, we see how play is both a playful activity, but also an important mechanism for more serious endeavors. This might look like an Autcraft member creating a series of YouTube videos of their game play as an anti-bullying campaign. Or this might be a member of ARMY creating a thread of edited BTS content to highlight the international sign the band used in their Permission to Dance video.

Both communities are also doing the work of correcting misconceptions and pushing back against stigma about themselves. These misconceptions occur because outsiders do not understand the community (often harboring sexism, misogyny, racism, and ableism towards both communities). Particularly, because these are communities of play, they are also often dismissed as ultimately inconsequential by outsiders. This is something both communities would vehemently protest, and do.

Creating Access to Play

Together, these studies show how communities leverage their playful qualities to appropriate and modify the technological and social make-up of the group in order to accommodate a diverse set of community members. From this, we are mostly left with more questions about “play” and “access.” Where is play taking place and can we support ideas of play for the sake of play at the same time play is also being used for more serious business? How is access being created in these various social spaces and what can communities do when they are at the mercy of the technology available to them?

In both communities, we see play being the platform for serious, even life-impacting, interests of community members (e.g., anti-bullying campaigns, grappling with both community-wide and individual trauma). With the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, these communities became that much more important for its members, as they became the only means of socializing and forming relationships with people outside their homes and places of work. These playful communities were not just a place of leisure or a creative outlet. They are also a place to form meaningful connections with other people.

At the same time, these playful communities are addressing various questions of access. In this talk, I started to illuminate some of the ways communities accommodate disabled community members. The work these communities are doing should be noted because how communities play and what that play is doing for members of communities can be a starting point for understanding these otherwise marginalized groups.

And you can watch a pre-recorded version of the presentation here:

References

1. @bock_twt. 2020. Bantam Seoyeondon: BTS ARMY Shenanigans. In 2020 Rhizome Connect Virtual Conference and Convention. Retrieved September 5, 2021 from https://rhizomeconnect.com/2020/expo-hall/shenanigans/

2. So Yeon Park, Nicole Santero, Blair Kaneshiro, and Jin Ha Lee. 2021. Armed in ARMY: A Case Study of How BTS Fans Successfully Collaborated to #MatchAMillion for Black Lives Matter. CHI 2021: 14.

3. Kathryn E. Ringland. 2019. A Place to Play: The (Dis)Abled Embodied Experience for Autistic Children in Online Spaces. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300518

4. Kathryn E. Ringland, Arpita Bhattacharya, Kevin Weatherwax, Tessa Eagle, and Christine T. Wolf. 2022. ARMY’s Magic Shop: Understanding the Collaborative Construction of Playful Places in Online Communities. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

5. Kathryn E. Ringland, Christine T. Wolf, Heather Faucett, Lynn Dombrowski, and Gillian R. Hayes. 2016. “Will I always be not social?”: Re-Conceptualizing Sociality in the Context of a Minecraft Community for Autism. In CHI 2016.

6. Tanya Titchkosky. 2011. The Question of Access: Disability, Space, Meaning. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

I am happy to share that our article for the ACM XRDS Magazine is now available.

“You’re my best friend.”: finding community online in BTS’s fandom, ARMY

The COVID-19 pandemic was a time of unexpected isolation for many, as well as a time fraught with uncertainty. In this article, we explore how many turned to playful online communities across a number of social media platforms as a place of connection and support.

You can find more information about my research with ARMY: https://kateringland.com/btsarmy/

-

research-article

“You’re my best friend.”: finding community online in BTS’s fandom, ARMY

The COVID-19 pandemic was a time of unexpected isolation for many, as well as a time fraught with uncertainty. In this article, we explore how many turned to playful online communities across a number of social media platforms as a place of connection …

Just over a week ago, I pulled out of a conference that I was meant to be presenting at this week. So, instead of having a jam-packed week full of presentations and research, I spent the time reflecting (and taking some extremely needed downtime). Now that I’ve taken that time, I wanted to reiterate my commitment to my community in my community-based research.

To be clear: My community in this discussion is BTS and ARMY. I can get a lot more detailed on what that means, but suffice to say this means the people in online and offline spaces who identify as OT7 ARMY. (Happy to talk with you more if you’re curious, just setting the stage for this blog.)

Some of this will be repeating this thread on Twitter and also this thread, but wanted to have one place where this was housed that I (and others) could reference.

Why Me?

I am an academic (I received my PhD in 2018 and now work as a professor) and I study how people use technology in their everyday lives. My expertise is in social platforms and play. What this means is I study games and other social media, but I also keep tabs on other technology.

I research communities and focus on how people interact with one another, how they make and keep relationships, and how the platforms they use help people support each other.

I also have a focus on disability and disability activism. I am myself disabled and use that as a lens to approach all of my work.

I work in communities I care about. I’ve written about this in other threads, but this work takes a lot of time/energy and very careful planning. I wouldn’t do this if I didn’t deeply care about this community.

As a disabled, neurodivergent scholar, I am very very aware of what it means to be othered and marginalized. With that experience, I try to bring compassion & understanding to everything that I do.

Why Research ARMY?

I have several reasons.

ARMY is amazing and the amount of work that happens in this community has already been noticed by outsiders. I hope to highlight some of this, as well as finding out how we can design technological platforms to better support ARMY activities.

I study play and care, which are both things that ARMY excel at. I want to help other people see and understand that about our community.

People are already researching ARMY, whether members of ARMY like it or not. I would love it if the people doing the research were actually ARMY, so they could better contextualize their findings. Worse are the people (who we’ve mostly seen in the form of journalists, but some researchers as well) who have a bias against ARMY and seek to prove it through their research. I do research to give a different perspective.

People are dismissive or ARMY. We know this. By having published research, I hope that we can have concrete things to point people to when they are like this. I have found with other groups I have done research with, that having the published research is a way to showing legitimacy in the face of critics.

What Now?

I am currently conducting my research in my day-to-day life as an ARMY. What does this mean? I spend a lot of time observing what goes on around me and reflecting on it. I write a lot. Most of my writing goes unread by everyone except me. However, eventually some of my writing ends up in blogs like this one or articles that get reviewed by other researchers.

In fact, I have a survey open right now for ARMY to take. I am hoping to combine survey results with my own ethnographic work to improve the reach of my research and to help me triangulate some of my findings.

Survey is here: https://tinyurl.com/BangtanSurvey

I am also extremely committed to making sure ARMY also have all the interesting findings from my work. There are actually lots of things I’m learning and seeing that the research community doesn’t even care about (their loss). So I’m releasing those as I have time to put them together. Here’s an example video I made last week during my downtime.

How Do I Ensure ARMY Isn’t Harmed?

I have taken many precautions in my work to make sure that ARMY and BTS are not harmed to the best of my ability. I’m human and I am sure there will be times this isn’t perfect. However, I still do my best. I’m going to end this article by listing some of the things I have done or plan on doing in this regard.

- Transparency. Wherever possible I am transparent about what I am doing and how I am doing it.

- Care with who I am sharing any data and what they actually have access to. When it comes to tweets, for example, I do not have any direct quotes from ARMY in my published work. I do not include usernames unless I’ve been given very explicit permission (this has only happened once, for a very specific reason, and I didn’t user the full username).

- Making sure the community (and in this case BTS) are discussed respectfully and within community norms. (Yes, I have had to fight on this and I will continue pushing back.)

- Ensuring the places I am presenting about ARMY are safe for ARMY. This means pulling out of conferences and publications if I need to.

- Making sure there is enough context and historical background when discussing anything about communities.

This blog will be a living document that I will come back to as needed in order to update as I work. I’m constantly iterating on my process and love learning from my community!

More about my research here: https://kateringland.com/btsarmy

We will be presenting this preliminary work at the CSCW 2021 workshop, “Future of Care Work: Towards a Radical Politics of Care in CSCW Research and Practice.”

There has been a recent effort to expand how we think about and design for care in digital spaces—including theorizing about care beyond formal or medicalized activities [1, 8, 9]. But there still remains unanswered questions about care in playful spaces, especially for adults. What types of care occur in these spaces? Our study examines this question by exploring fandoms on social media. We define fandoms as playful (online) communities that align around a particular interest (e.g., specific media or a person). Fandoms are meant to be for fun or pleasure and are often entirely separate from other parts of a person’s life, at least overtly [3].

In particular, our study in an ongoing ethnographic investigation of ARMY, a fandom that supports the Korean music group BTS. ARMY and BTS has piqued the interest of both mass media and academia in the past for some of their altruistic engagements including include supporting their community, artists, music, and social causes [2, 6], as well as BTS’s positive impact on mental health [5]. The care activities this community engages in is also bidirectional with BTS and ARMY caring for each other mutually. ARMY engages in many practices of care, even towards members of the band, defending them when controversies arise or posting words of concern for members’ health.

For this work, we are adopting a decolonial lens to understand care activities as relational and epistemically privilege the members of ARMY. This is especially important as ARMY has experienced delegitimization and stigamatization, including through discriminating on the basis of gender or age (e.g., [4, 7]). The need for a decolonial lens is heightened because of the origin of BTS (i.e., Korea) and the diversity of ARMY membership [2]. In this work, we aim to expand our understanding of care both by looking at playful online spaces where adults socialize and seek informal community support and through a decolonial perspective during data collection and analysis.

AUTHOR BIOS

Kathryn Ringland, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at the University of California Santa Cruz. Her areas of interest include human computer interaction, games studies, and critical disability studies.

Christine Wolf, JD, PhD. is interested in the intersection of CSCW, accessibility, and the future of work.

Tessa Eagle Tessa Eagle (she/her) is a third-year Ph.D. student in Computational Media at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She conducts research within human computer interaction and digital mental health.

Kevin Weatherwax is a fourth-year PhD student in Computational Media at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Presently he is researching satisfaction in robot-mediated collaborations, expressive curiosity for interaction design, and parasocial engagements with nonhuman agents as assistive technology for neurodivergent populations.

REFERENCES

[1] Cynthia L. Bennett, Daniela K. Rosner, and Alex S. Taylor. 2020. The Care Work of Access. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, Honolulu HI USA, 1–15.

[2] BTS ARMY Documentary Team [@amidocumentary], On Wings of Love [@OWOLMovie], and Research BTS [@ResearchBTS]. 2020. BTS ARMY CENSUS. https://www.btsarmycensus.com/.

[3] Mark Duffett. 2013. Understanding Fandom: An Introduction to the Study of Media Fan Culture. Bloomsbury, New York.

[4] Emily. 2021. Fangirls, Fandom, and BTS – A Letter to the ARMY.

[5] Jin Ha Lee, Arpita Bhattacharya, Ria Antony, Nicole Santero, and Anh Le. 2021. “Finding Home”: Understanding How Music Supports Listerners’ Mental Health Through a Case Study of BTS. In Proc. of the 22nd Int. Society for Music Information Retrieval Conf. 8.

[6] So Yeon Park, Nicole Santero, Blair Kaneshiro, and Jin Ha Lee. 2021. Armed in ARMY: A Case Study of How BTS Fans Successfully Collaborated to #MatchAMillion for Black Lives Matter. (2021), 14.

[7] Lady Flor Partosa. 2021. We Are Not Robots: A Preliminary Exploration into the Affective Link between BTS x ARMY. The Rhizomatic Revolution Review [20130613] 2 (March 2021).

[8] Austin Toombs, David Nemer, Laura Devendorf, Helena Mentis, Patrick Shih, Laura Forlano, and Elizabeth Kaziunas. [n.d.]. Sociotechnical Systems of Care. CSCW 2018 ([n. d.]), 7.

[9] Austin L. Toombs, Shaowen Bardzell, and Jeffrey Bardzell. 2015. The Proper Care and Feeding of Hackerspaces: Care Ethics and Cultures of Making. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’15). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 629–638.

The month of May is proving to be a whirlwind and we are only 6 days in. But I wanted to take a moment out of my day to write down some of my reflections and experiences from my first ever BTS Conference.I have been to a lot of different conferences over the years, but this one definitely had a different kind of vibe and I loved it. This blog is more my overall reflections of the experience of the conference, rather than getting into the details of the research. If you want to see more of the blow-by-blow of my experience, I’ve added my conference tweets at the bottom of this post.

To get this out of the way…

I will admit that I had some concerns before the conference started given the tension over research in the community and newbie researchers talking to magazine outlets that I shall not name here. A part of my goal for tweeting during the conference (and this blog) was to increase the transparency to which these research activities are to ARMY as a whole. I want concerns and questions about research, the purpose, how it works, what the outcomes are answered before they get to the point that ARMY are only hearing about it after the fact in a media outlet. Fortunately, everyone at the conference (and from what I saw on Twitter) were open, transparent and understanding of one another.

Now the good stuff!

Because the conference was by topic rather than discipline, it had a diverse range of fields and types of people represented (from hobbyists to full professors). For me personally, this is my favorite kind of space to be in. There is something so magical about being in interdisciplinary spaces. Everyone brings their own expertise and backgrounds to the room to discuss specific topics and the conversations that are unleashed are always rewarding. Are there some frustrations and miscommunications? Sure. But by far, diversity and interdisciplinarity is always the best option.

Partially because the audience was both interdisciplinary and not necessarily “academic” (in the ivory tower sense of the word), the content and talks were approachable and accessible. The keynote speech on the first day by Dr. Crystal Anderson set a wonderful tone that I feel pervaded the whole rest of the conference. Right from the start, ARMY as the fans were centered as the experts in this space – not journalists or other academics. And certainly not nameless older abled white male academic whose opinion is so often valued by those outside the community (insert eye roll here).

Researchers studying both BTS and ARMY, at least at this conference, were here because they value both BTS and ARMY – many opened their talks by giving their backgrounds not just as researchers, but as ARMY. It was refreshing. Honestly, between the open passion about being ARMY and the diversity (oh the wonderful diversity) of panelists and attendees really made this the safest I have felt at a conference, ever.

The big take-away from the conference, for me, was: Vulnerability and being open about struggles helps to create a space for us to care for each other (both for BTS and ARMY). In online spaces, there are real people with their own pain and struggles behind the screen. Care is loving yourself & taking care of your community.

The conference organizers (next year’s organizers or other research ARMY organizing these kind of events, feel free to slide me a DM if you want to talk about making the event more accessible) did a wonderful job of setting the tone and I came away with lots of ideas for my own research. I met a lot of other passionate ARMY also interested in furthering the same goals of bringing knowledge to our community. Overall, the whole experience left me motivated and with a feeling that I’m really glad I am both ARMY and researcher. Borahae!