As part of the Future of Childhood blog series for the Joan Ganz Cooney Center, I have written some of my own thoughts on the future of childhood.

Check it out here: https://joanganzcooneycenter.org/2020/05/06/kathryn-e-ringland

As part of the Future of Childhood blog series for the Joan Ganz Cooney Center, I have written some of my own thoughts on the future of childhood.

Check it out here: https://joanganzcooneycenter.org/2020/05/06/kathryn-e-ringland

Preview: Autism is a medical diagnosis that has attracted much attention in recent decades, particularly due to an increase in the numbers of children being diagnosed and the changing requirements for getting the diagnosis. In parallel online communities around autism—both those supporting individuals, families seeking treatment and those supporting embracing the autism identity—have grown. Other work has shown support groups can be useful for those encountering hardship in their lives. In this paper, I illuminate the tension in claiming the autistic identity within this community. The walls of the community work to keep community members safe, but also set them apart from others on the internet. I see that the Autcraft community goes beyond being a support group for victims of targeted violence, to one that redefines and helps community members embrace their own autistic identities.

Autism has been the topic of much public concern in recent decades, especially since the sensationalized “autism epidemic” swept through the media. As a medical diagnosis, autism focuses on challenges for individuals; such as whether they are verbal, make eye-contact, or are sensitive to change. Often, as a label, autism is given to youth in order to gain accommodations in school, or for medical treatment. Autistic youth often experience various ways in which this label is used to disempower and disenfranchise them.

This is the case for many youth that are a part of an online community, “Autcraft,” a community centered on a Minecraft virtual world for autistic youth. While those with autism are often the target of harassment and violence in online spaces, the Autcraft community has been actively engaged in making themselves a safe space for youth with autism. Beyond simply keeping bullies out, however, the community has taken the label of “autism” and turned it into something positive—a label worth identifying with.

In the Autcraft community, I have found that the label acts both as a target and as a way for community members to redefine their identities.

Concerns over safety of children is an ongoing concern for parents and other caregivers. This is particularly true of those with autistic children, as those with autism tend to be targeted both by their peers and by strangers [32]. Much like other marginalized groups, “autism” is used as a derogatory term. Further, threats of violence can be found across the internet, including in the comments section of YouTube videos, a site used by Autcraft community members. This is especially meaningful as other related work has shown the embodied experience in these online spaces can be as impactful as in physical spaces [29]. Unfortunately, these threats of violence can also result in actual physical harm.

Harassment, threats of violence, and comments about autistic people killing themselves can have a large impact on those targeted, such as additional stress and other psychological harm [22]. The harm, however, does not stop with verbal and written threats. Like other marginalized communities, those with autism face the very real threat of violence against them [14,15].

Here is a video related to these threats of violence in the autistic community at large.

There is evidence throughout the

Autcraft community of those who are expressing their autistic identity. Autcraft

community members may be learning to understand and accept themselves or their

child as an autistic individual, but they are also learning to deal with

challenges found outside the Autcraft community where they may not find

themselves accepted and face opposition.

[alt-text for embedded tweet picture: autsome, adjective, Having autism and being extremely impressive or daunting; inspiring great admiration. “My autsome child makes me proud everyday!” synonyms: breathtaking, awe-inspiring, magnificent, wonderful, amazing, stunning, staggering, imposing, stirring, impressive; informal extremely good; excellent. “The band is truly autsome!”]

Adopting “autism” and various forms of the word—as seen in the name of the community “Autcraft”—lends to a sense of identity with others who have the same or similar medical diagnosis. Aside from using “aut” or “autistic” in their user names (i.e., the names that are displayed with their avatars and forum posts, rather than a real-world name), the Autcraft community displays this acceptance through the creation of autism-centric words, such as “autsome.” According to a community post, “autsome” means, “Having autism and being extremely impressive or daunting” and “extremely good; excellent.” Scholars have described how those with disability are often held to a higher standard and those who are “extreme” tend to be held up as inspirational. This type of “inspiration” frames disability as something to be overcome, while achieving difficult objectives. However, I argue that having language such as “autsome” is meant to be inspirational not for others looking in to the Autcraft community, but for the autistic children who are otherwise dealing with a barrage of negative language about autism. This reframes autism as an identity that is worth embracing, rather than overcoming.

Autcraft community members actively work to reshape the mainstream dialog about autism. First and foremost, members try to lead by example, following a set of tenets set out by community founders that encourage and promote good behavior. Community members also engage in outreach to both educate others and to make their own expressions of their autistic identities more visible to others. Members of the Autcraft community engage in activities—much like creating memorials for victims of violence—that purposefully shed light on the hardships they have faced. These efforts are examples of how those with marginalized identities fight back against oppression. As scholars, by listening to these community members and understanding their activities, we can begin to elevate the voices of those who have long been silenced.

For more details about our methods and findings, please see my paper that has been accepted to iConference 2019 (to appear in April 2019). Full citation and link to the pdf below:

Kathryn E. Ringland. 2019. “Autsome”: Fostering an Autistic Identity in an Online Minecraft Community for Youth with Autism. In iConference 2019 Proceedings. [PDF]

Acknowledgements: I thank the members of Autcraft for the warm welcome to their community. Thank you to members of LUCI for their feedback and special thanks to Severn Ringland for his diligent editing. I would also like to thank Robert and Barbara Kleist for their support, as well as the ARCS Foundation. This work is covered by human subjects protocol #2014-1079 at the University of California, Irvine. This work is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH115882). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Preview: Those with disabilities have long adopted, adapted, and appropriated collaborative systems to serve as assistive devices. In a Minecraft virtual world for children with autism, community members use do-it-yourself (DIY) making activities to transform Minecraft into a variety of assistive technologies. Our results demonstrate how players and administrators “mod” the Minecraft system to support self-regulation and community engagement.

A calming, quiet garden in Minecraft.

“Need a place to calm down? Quiet? Peaceful? Choose a Calm Room to visit here. In these rooms [t]here is no chat. It’s a place to relax. Visit any time.”

If a child finds face-to-face conversations challenging and feels isolated from their peers at school, where can they go to make friends? How can people use currently existing systems to help those with disabilities, including children with autism? We studied how one online community, Autcraft, through a variety of social media platforms, augments and extends current platforms and transforms them into assistive technology for children with autism.

Autcraft is a Minecraft community for children with autism and their allies run by parent volunteers. The goal of the Autcraft community is to have a safe space for children with autism to play Minecraft free from harassment and bullying (for more information visit the Autcraft website). As part of our study, I have been conducting an on-going ethnography within the community (see our paper for details). This study included analysis of activity within the Minecraft server, forums, website, Twitter, Facebook group, YouTube, and Twitch.

Our analysis demonstrates how players and administrators “mod” the Minecraft system to support self-regulation and community engagement. This work highlights the ways in which we, as researchers concerned with accessible and equitable computing spaces, might reevaluate the scope of our inquiry, and how designers might encourage and support appropriation, enhancing users’ experience and long-term adoption.

Autcraft community members have modified Minecraft to do the following to help players internally regulate themselves and externally manage their engagement with others:

Individual players appropriate the Autcraft virtual world to suit their own needs, shaping their virtual environment, embodied experience, and, in time, influencing the overall experience for everyone in Autcraft. As the children worked within the confines of the virtual world to make their environment more usable by appropriating with what was available, administrators are able to then iterate on these appropriated instances to re-appropriate the software itself. Thus, administrators, following the cues of the children within the virtual world, are able to instantiate these appropriations and make them available to everyone on Autcraft.

As a group, children with autism are doubly disempowered: both as children and as people living with disabilities. Here, however, we see how this kind of technological openness allows them to customize and create their own play spaces, a type of autonomy that is inherently empowering. This work explores how designers and researchers can learn by observing how even the youngest of users augment and appropriate mainstream technology to become assistive in their daily lives. This work highlights the ways in which researchers concerned with accessible and equitable computing spaces might reevaluate their scope of inquiry and how designers might encourage and support appropriation, enhancing the individualized experience and long-term adoption of assistive devices and systems. The appropriations we observed in Autcraft point to a future model where child-initiated modifications can guide research and design, providing greater access for disempowered communities.

For more details about our methods and findings, please see our full paper that has been accepted to ASSETS 2016 (to appear in October 2016). Full citation and link to the pdf below:

Kathryn E. Ringland, Christine T. Wolf, LouAnne E. Boyd, Mark Baldwin, and Gillian R. Hayes. 2016. Would You Be Mine: Appropriating Minecraft as an Assistive Technology for Youth with Autism. In ASSETS 2016. [PDF]

Acknowledgements: We thank the members of Autcraft for the warm welcome into their community. We also thank members of LUCI and the anonymous reviewers for their feedback on this paper, and Robert and Barbara Kleist for their support. This work is covered by human subjects protocol #2014-1079 at the University of California, Irvine.

Acknowledgements: We thank the members of Autcraft for the warm welcome into their community. We also thank members of LUCI and the anonymous reviewers for their feedback on this paper, and Robert and Barbara Kleist for their support. This work is covered by human subjects protocol #2014-1079 at the University of California, Irvine.

Preview: Members of the Autcraft community for children with autism and their allies use a variety of social media platform, centered around Minecraft. The community’s use of various technologies facilitates the expansion of how members can socialize with one another, giving them opportunity to explore their own sociality, expand how they would like to be able to socialize, and deepen their connection with other members of the Autcraft community.

Autcraft community members playing a game together.

“I love being a member of the [Autcraft] community and love spending time with my ‘family’ here. … A place I was accepted for … just being ‘different’ than others.”

If a child finds face-to-face conversations challenging and feels isolated from their peers at school, where can they go to make friends? Online communities have the potential to support social interaction for those who find in-person communication challenging, such as children with autism. Unfortunately, online communities come with their own set of problems – cyberbullying is particularly troubling. We studied how one online community, Autcraft, through a variety of social media platforms, practices and defines how they are social.

Autcraft is a Minecraft community for children with autism and their allies run by parent volunteers. The goal of the Autcraft community is to have a safe space for children with autism to play Minecraft free from harassment and bullying (for more information visit the Autcraft website). As part of our study, I have been conducting an on-going ethnography within the community (see our paper for details). This study included analysis of activity within the Minecraft server, forums, website, Twitter, Facebook group, YouTube, and Twitch.

Our analysis demonstrates how members of the Autcraft community search for, practice, and define sociality. These results indicate more broadly how people may increasingly find new ways to express themselves and create a sense of community as emergent forms of media change the nature of our social landscape. Our exploration of Autcraft adds to a growing body of work about social platforms by showing how flexible, multimodal communications not only “keep the game going” but also can have profound effects for self-expression and feelings of social belonging.

Autcraft community members engage in the following:

By using various platforms, members of the Autcraft community are able to form deeper friendships with one another, if so desired. Being able to foster these relationships across the myriad platforms creates cohesion in the community. Two members may meet through an advertisement on the forums for builders, build a project together, and then go on to create YouTube videos together of the experience. This facilitates the expansion of how members can socialize with one another, giving them opportunity to explore their own sociality, expand how they would like to be able to socialize, and deepen their connection with other members of the Autcraft community.

For more details about our methods and findings, please see our full paper that has been accepted to CHI 2016 (to appear in May 2016). Full citation and link to the pdf below:

Ringland, K.E., Wolf, C.T., Faucett, H., Dombrowski, L., and Hayes, G.R. “’Will I always not be social?’: Re-Conceptualizing Sociality in the Context of a Minecraft Community for Autism”. Proceedings of the 2016 ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ACM (2016). [Acceptance Rate: 23.4%] [PDF]

Acknowledgements: We thank the members of Autcraft for the warm welcome to their community. We would like to thank members of LUCI for their feedback on this paper. We would also like to thank Robert and Barbara Kleist for their support. This work is covered by human subjects protocol #2014-1079 at the University of California, Irvine.

Acknowledgements: We thank the members of Autcraft for the warm welcome to their community. We would like to thank members of LUCI for their feedback on this paper. We would also like to thank Robert and Barbara Kleist for their support. This work is covered by human subjects protocol #2014-1079 at the University of California, Irvine.

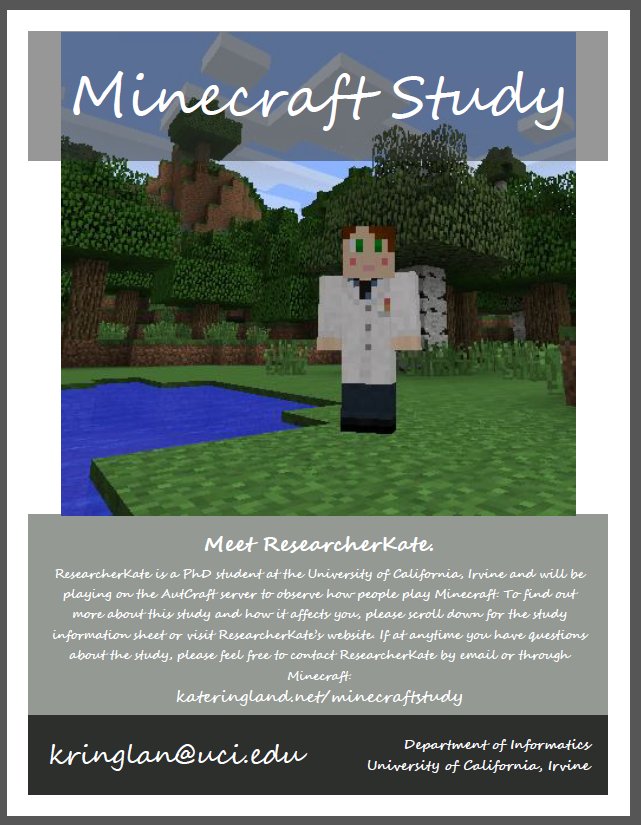

My intention with these blog posts is to have a sort of informal record of my time spent in Autcraft. They will be my beginnings, in a way, of creating my overall narrative of my experience. I will be creating much more formal documentation in the form of conference papers and journal articles, but here I want to create a space that is more open to dialogue and discussion. I also want the community to know that I am completely open and willing to share my thoughts and findings as much as I want to hear the thoughts of those in the community. My hope is to be able to tell the story of Autcraft and to be able to, through technology, expand on what it has given the autism community if I can.

My first week in the Autcraft community has been an extremely humbling experience. As I made my first timid steps into the unknown, I was greeted with open arms. A good number of people have given me encouragement, offered to help, welcomed me and offered friendship, and thanked me. I feel like I should be the one thanking every single member of the Autcraft community for allowing me to be among them.

I feel like I have accomplished a lot in the few hours I have played over the last week: I’ve built a modest office, explored many different areas, gone mining, died in lava, played Hide and Seek with other players, marveled at all the amazing things other players have built, played Paint Ball with other players, and died falling from a giant pink pony. All and all, a very busy, but successful week.

Fell off from the top of a giant pink pony and died. Admittedly a first for me.

I have been struck by the many different ways in which players communicate in Autcraft. There is text chat, but there is so much more. Players also communicate via their characters (how they look and through their movements), via their constructions, via signs littered throughout the world, and more. I am sure those that have a limited understanding of autism would be very surprised to hear that these players are communicating at all. And while I am still in the very early stages of my research, I can assure anyone reading this that these players are communicating- in a varied and rich format.

I will close with that for this week. Please stay tuned and feel free to email me at kringlan [at] uci [dot] edu with any questions about my work. Thanks and keep on building!

My name is KateRingland and I am a PhD student in Informatics at the University of California, Irvine. I will be conducting observations of players in Minecraft. For the most part, this will just look like I’m playing the game like everyone else. However, I will be taking notes of my experiences and possibly screen shots. I will not be recording any identifiable information. I will not record any real names or real screen names. If I take a screen shot, I will blur out anything that would identify an individual player.

What are you looking for during your observations? I am mostly just watching to see how players on Minecraft interact. I would also like to explore the various ways in which players communicate during game play. I am hoping this research leads to helping children with Autism Spectrum Disorder have a supportive, fun environment to play in.

I am now conducting interviews! Find out more information HERE.

Please email me at kringlan [at] uci [dot] edu if you have any questions.

CLICK HERE FOR ADDITIONAL STUDY INFORMATION.

Our first paper from this project is published at Computer Supported Collaborative Work (CSCW) 2015, titled ‘Making “Safe”: Community Centered Practices in a Virtual World Dedicated to Children with Autism’.

Last Updated: June 1, 2015.

© 2024 Kate Ringland, PhD

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑