When Fandom Meets Fascism: Weaponizing Norms in the BTS ARMY Community

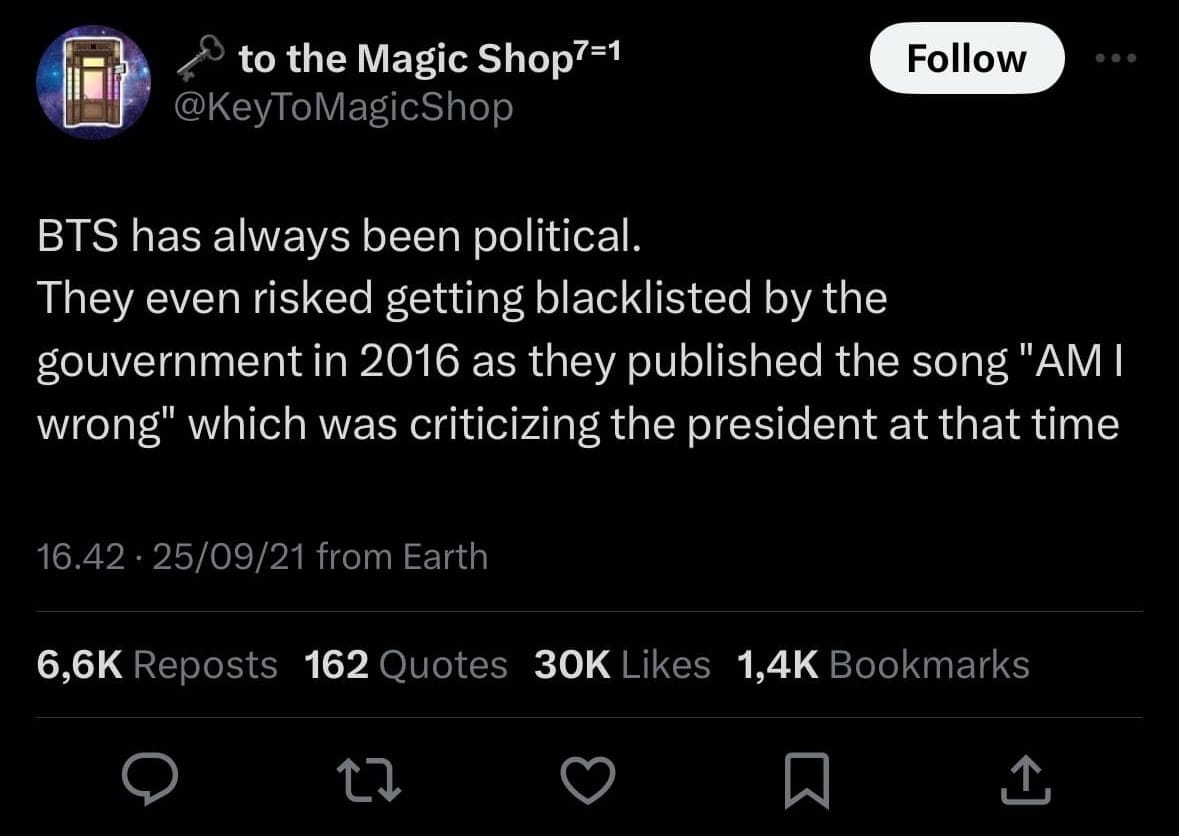

In 2020, BTS ARMY (BTS’s fandom) raised $1 million for Black Lives Matter in a single day, matching the band’s own donation. The media hailed it as a watershed moment for fandoms as engines of activism—the proof that passion and purpose could collide to create real-world change[1]. But behind the headlines lay a more complicated story. Before BTS’s donation, much of the fandom was divided, with significant tension along racial lines as many ARMY resisted engaging with BLM. Black ARMYs were under attack from fellow ARMY as they worked to organize for different GoFundMe campaigns and online campaigns within and outside of the fandom space. It wasn’t until the band took a public stand that the fandom followed suit, transforming what began as a fractured effort into a celebrated narrative of collective action.

This uneasy dynamic—where activism emerges only after external validation—has echoed throughout ARMY’s history. And now, it comes to a head with the HYBE boycott, a movement aimed at holding BTS’s parent company accountable for its Zionist ties. The boycott forces a reckoning with the contradictions at the heart of ARMY’s activism: Can a movement fueled by consumerism dismantle the systems it feeds? And when loyalty to a favorite band conflicts with a commitment to justice, where does a fan’s responsibility lie?

This blog explores the HYBE boycott as both a case study and a cautionary tale—a moment that reveals the limits of fandom-based activism under capitalism and the fractures that emerge when personal values collide with collective identity.

The ARMY Model: Fandom as Activism

Fandoms, especially BTS ARMY, often function as experimental models of activism. They combine the power of collective identity with the reach of digital platforms, creating spaces for rapid mobilization around shared values. As Henry Jenkins describes in Participatory Culture[1], fandoms blur the lines between consumers and producers, allowing fans to coalesce into communities capable of action. ARMY exemplifies this dynamic, leveraging its global network to support causes like raising $1 million for Black Lives Matter or driving voter education in the 2021 Chilean election.

Jenkins, Henry. Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture. United Kingdom, New York University Press, 2006. ↩︎

However, ARMY’s activism is inextricably tied to consumerism. These celebrated moments of collective action are often fueled by the very mechanisms of capital—donations, merchandise purchases, and streaming campaigns. This raises a critical question: Can activism within fandoms ever truly transcend the systems of consumption that define them?

While ARMY has mobilized significant funds for justice-oriented causes, its activism often mirrors the capitalist structures it seeks to challenge. Merchandise sales, album purchases, and streaming efforts don’t just bolster ARMY’s impact—they underpin its very identity. This reliance on consumer-driven participation raises difficult questions about whether activism in fandom spaces can escape the pervasive influence of capitalism.

As a global fandom, ARMY also reflects a wide range of voices and values, which ensures both richness and friction. Political issues often resonate differently across cultural and national contexts. Western ARMY members, for instance, may interpret activism through a lens of individualism, while fans in East Asia or the Global South approach these issues with different cultural frameworks. While this diversity contributes to the richness of the community, these differences also lead to fragmented responses and inconsistent priorities, challenging ARMY’s ability to act cohesively.

ARMY’s activism frequently straddles the line between performative and substantive[1]. Trending hashtags and symbolic gestures amplify marginalized voices but can fall short of driving systemic change. More tangible actions—like the HYBE boycott, which we discuss below—test the community’s ability to move beyond surface-level solidarity. These tensions become even starker when considering how ARMY’s activism is selectively amplified. Voices that align with the fandom’s collective identity—often shaped by white-centric cultural norms[2]—are prioritized, while more contentious or systemic critiques risk being dismissed or silenced.

Lynch, Kimery. Complicating Monolithic Western Media Narratives of the BTS ARMY’s Fandom Activism During the 2020 #BlackLivesMatter Movement. ↩︎

Pande, Rukmini. “Who Do You Mean by ‘Fan?’ Decolonizing Media Fandom Identity.” A Companion to Media Fandom and Fan Studies, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2018, pp. 319–32. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119237211.ch20. ↩︎

This dynamic underscores the dual nature of ARMY’s collective identity: it can empower the marginalized while also adhering to exclusionary norms. The emphasis on traditional “politeness” and respectability often suppresses dissent and reinforces white-centric standards of activism[1][2]. When fandom values are truly tested—such as with deeply polarizing issues like the HYBE boycott—the cracks in this model of action become impossible to ignore.

The HYBE Boycott Explained and Why It Matters

The HYBE boycott represents one of the most contentious and defining moments in ARMY’s history. What began as a grassroots call to action now lays bare the fractures within the fandom’s collective identity, challenging everything from its values to its methods of activism. For a deeper understanding of the origins and details of the boycott, see Paste Magazine’s coverage of Palestinian K-pop fans organizing in solidarity with their people (https://www.pastemagazine.com/music/k-pop/as-the-genocide-in-gaza-continues-palestinian-k-pop-fans-organize-for-their-people). We will have additional resources linked at the bottom of this article.

*Note: For simplicity, this article will refer to the two sides of the HYBE boycott debate as "pro-boycott" and "anti-boycott." However, the reality is far more nuanced. The groups on each side are large and diverse, making this issue much more complex than a binary divide. Additionally, supporting or opposing the boycott does not inherently mean taking a stance for or against a particular group of people (e.g., Palestine). That said, many do conflate these positions, so we will aim to clarify language where necessary in this article.

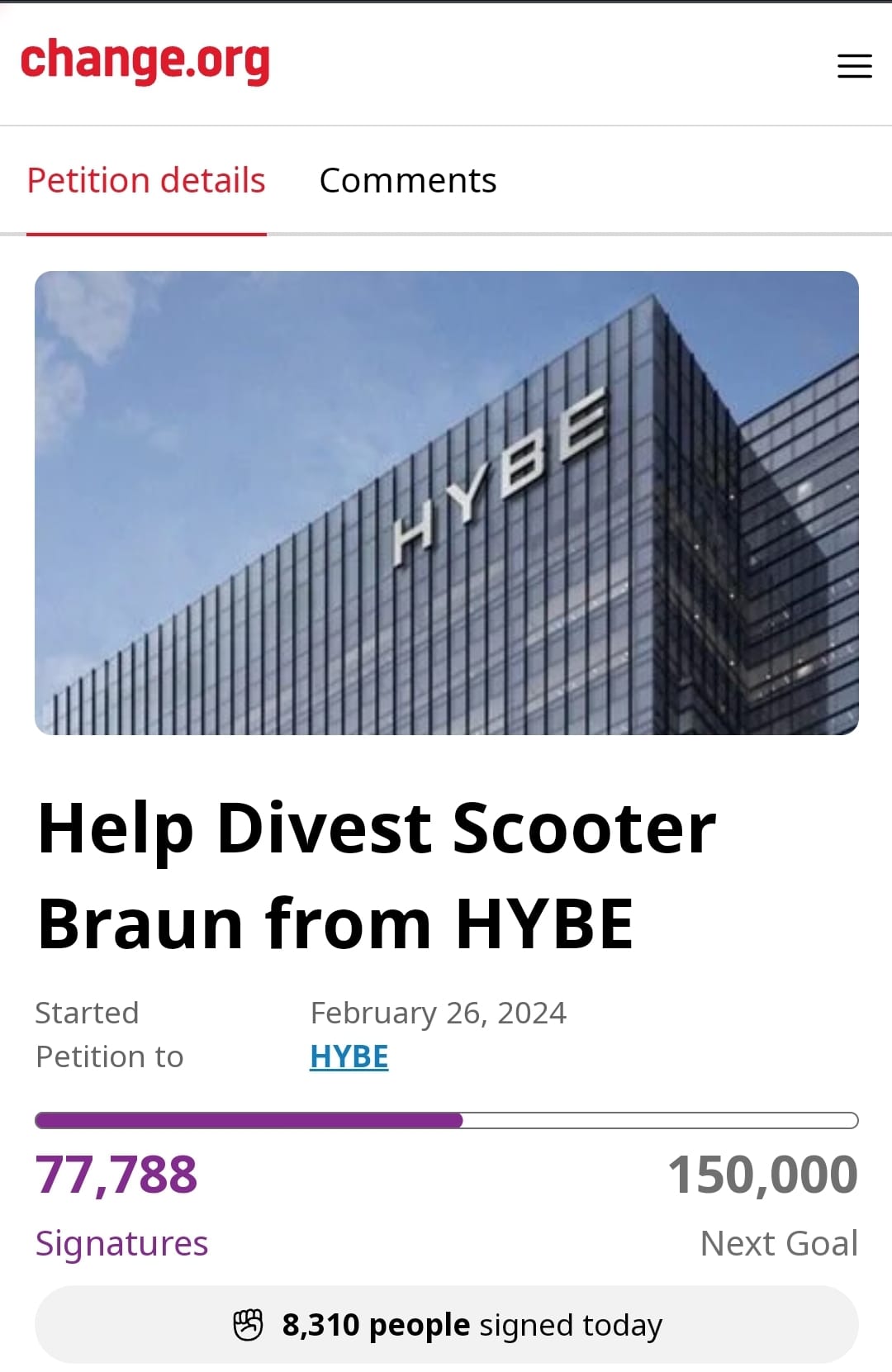

The boycott originated from HYBE’s ties to Zionist organizations at a time when international calls were being made to pressure a cease of the genocide by Israel in Palestine[1]. CEO Scooter Braun’s vocal support for Zionism, paired with HYBE’s active censorship of pro-Palestinian content on its platforms (such as Weverse), catalyzed outrage among fans. Palestinian and pro-Palestinian ARMYs, along with their allies, called for a boycott of HYBE—a refusal to purchase merchandise, stream music, or contribute financially to a company complicit in what they view as systemic injustice. For many supporters, this movement is a natural extension of ARMY’s history of justice-oriented activism.

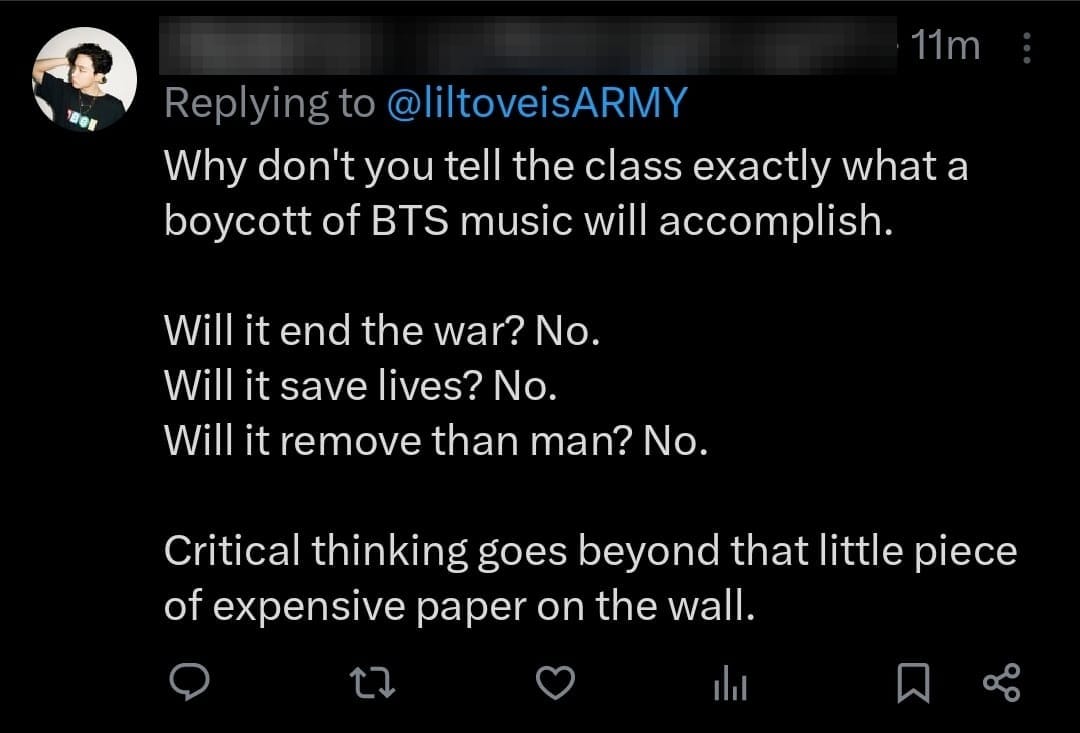

But, instead of the boycott unifying ARMY around a social justice cause—it’s divided it. Critics argue that the boycott is misdirected, harmful to BTS’s career, or even unnecessary. These disagreements have escalated into a full-blown ideological rift, with pro-boycott ARMY facing backlash that has turned hostile and, at times, violent. Doxxing, coordinated harassment, and mass reporting have targeted those advocating for the boycott, effectively silencing many voices. Both authors of this blog were doxed during the height of the backlash, a testament to the extreme lengths some fans will go to in defense of their position.

At the heart of the conflict is a deeper question: What does loyalty to BTS mean, and where does it end? For anti-boycott ARMY, the act of streaming, buying, and monetarily supporting BTS is inseparable from their identity as fans. In this framework, boycotting feels like a betrayal—not just of the band but of the fandom itself. Monetary participation has long been viewed as the ultimate proof of fanship (despite assurances that those who are economically not able to make purchases still matter in the fandom), and deviating from this norm places boycotters at odds with entrenched fandom hierarchies.

This dynamic underscores a troubling reality: ARMY’s collective identity is deeply intertwined with capitalism. Buying albums, streaming music, and purchasing merchandise aren’t just actions—they’re rituals that signify belonging. The boycott’s challenge to this model of participation threatens the very fabric of the fandom, making it far more polarizing than ARMY’s previous activist campaigns. Unlike raising money for Black Lives Matter or voter education, boycotting requires fans to withhold their capital—an act that directly contradicts the fandom’s traditional forms of engagement.

Adding to the tension is the way ARMY’s internal power dynamics play out in real time. While pro-boycott voices amplify the moral imperative to act in solidarity with Palestine, anti-boycott ARMYs frequently sideline these critiques. This has led to a disturbing trend of violently policing pro-Palestinian voices while ignoring, or even defending, the presence of Zionist accounts within the fandom. The privilege to prioritize BTS’s career over human lives reveals stark racial and cultural divisions within ARMY, where marginalized voices—particularly Palestinian and pro-Palestinian fans—are often dismissed or silenced.

What makes this conflict particularly troubling is how it reflects the fandom’s uneven moral compass. While ARMY has long celebrated its capacity for activism, the HYBE boycott has exposed deep cracks in this identity. Many fans appear to take their ethical cues exclusively from BTS themselves, rather than from an intrinsic commitment to justice. Without clear guidance from the band—who remain largely absent while fulfilling their military service throughout these events—these fans struggle to navigate complex moral questions independently. This reliance on external validation highlights a troubling dynamic: for some, ARMY’s activism is less about systemic change and more about reinforcing their loyalty to BTS.

The boycott isn’t just a moral litmus test for individual ARMY members—it’s a referendum on fandom-based activism as a whole. It asks uncomfortable questions about the limits of solidarity, the ethics of consumption, and the price fans are willing to pay for justice. As the boycott continues to unfold, it reveals the fragility of ARMY’s unity when personal values collide with collective identity. What could have been a moment of reckoning instead becomes a battleground, where fandom loyalty and accountability wage an uneasy war.

The Cost of Being a Fan: Consumerism in Fandom Spaces

For BTS ARMY, fandom participation often comes with a price tag—literally. From streaming campaigns to merchandise purchases, monetary contributions have become the primary metric for proving one’s devotion. This isn’t unique to ARMY, but the scale at which BTS fans operate sets them apart. Consumerism isn’t just a byproduct of fandom. It’s deeply embedded in its structure, shaping ARMY’s collective identity and reinforcing the systems it seeks to challenge.

ARMY’s economic influence is staggering. The fandom’s purchasing power fuels HYBE’s dominance in the global music industry, generating millions of dollars through album sales, merchandise, concert tickets, and streaming services. For example, in 2023, BTS Jimin’s Like Crazy reached #1 on the Billboard Hot 100, thanks to 254,000 digital song downloads and CD singles sold[1]—a figure that dwarfs typical sales in an industry now driven by streaming and radio play. This achievement wasn’t just about fandom dedication but required significant financial investment by individual fans, many of whom purchased multiple copies to boost sales figures.

This monetary participation extends to every corner of ARMY’s activities. K-pop albums aren’t just CDs—they’re collectible bundles that include photobooks, stickers, and, most notably, photocards. But one album is never enough. Fans often buy several copies to collect all the randomized photocards or to meet Billboard’s strict anti-bulk-buying rules (four purchases per transaction). This system encourages over-purchasing, with fans dumping excess albums or reselling them at discounted prices[1]. The photocard economy thrives on this cycle, creating a secondary market where rare or desirable cards fetch exorbitant prices[2]. Cards featuring popular members or unique poses can sell for hundreds—or even thousands—of dollars, turning what was once a sentimental keepsake into a hyper-capitalist trading commodity.

https://www.cbc.ca/radio/day6/k-pop-environmental-practices-1.6930864 ↩︎

If you're interested in hearing more, listen to our podcast episode about the fandom merch economy: https://youtu.be/uOVXFnkS4co ↩︎

But it doesn’t stop there. ARMY’s purchasing habits extend to BTS-branded products like BT21 (cartoon characters created by BTS) and TinyTan (miniature figurines of the band). These products range from waffle makers to Christmas tree ornaments, blurring the line between fandom and lifestyle branding. Even “beWATER with BTS,” a branded water line, epitomizes the fandom’s willingness to monetize every aspect of its identity.

A contentious example is Jin’s partnership with FRED Jewelry. FRED, a luxury jewelry brand with direct ties to Zionist individuals and institutions, became a flashpoint in the HYBE boycott. Despite calls to avoid these products due to their political implications, FRED-sponsored items worn by this BTS member sold out instantly, highlighting the tension between fandom loyalty and ethical responsibility. Fans who continue to purchase FRED products directly fund Zionist-linked entities, undermining the very values of justice and solidarity that ARMY claims to uphold. This case exemplifies how consumerism within fandom spaces can perpetuate systemic harm, even as fans celebrate their economic power as a force for good.

This hyper-consumerism comes with consequences. By prioritizing monetary participation as proof of fanship, ARMY inadvertently reinforces exclusionary hierarchies within the fandom. Fans who can afford to stream endlessly, buy concert tickets, or purchase every new product are celebrated as “true” ARMY, while those with limited financial means are dismissed or ostracized. Online, fans without “proof of fanship”—in the form of albums, streaming stats, or merchandise—are frequently ridiculed, creating a toxic environment that contradicts BTS’s messages of inclusion and solidarity.

These dynamics are especially troubling given the ethical implications of ARMY’s spending. HYBE’s revenue streams directly fund its global expansion and platform individuals like Scooter Braun, whose Zionist affiliations have made him a central figure in the HYBE boycott controversy. By knowingly participating in this economy, fans (unintentionally) fund systems that perpetuate systemic injustices, such as Zionism. Yet, for many, the pressure to prove loyalty to BTS through consumerism outweighs these ethical concerns. The boycott forces fans to confront this tension head-on (if they choose to reflect), challenging them to reevaluate their spending habits and what it means to be an activist in fandom spaces.

Even the global success of BTS’s music charts is tied to this consumerist model. BTS’s 2020 hit Dynamite spent 32 weeks on the Billboard Hot 100—an achievement that required months of fan-organized purchasing campaigns to maintain its chart position. This wasn’t just about celebrating a hit song. It was a deliberate effort to outdo the 31-week record of PSY’s Gangnam Style and solidify BTS’s legacy. The labor and financial toll on fans during this time were immense, yet the fandom’s competitive drive ensured the work continued.

Ultimately, much of ARMY’s collective identity revolves around its purchasing power. This model of fandom—where devotion is measured in dollars—raises critical questions about the ethics of consumerism in activist spaces. Can a fandom rooted in capital ever truly champion justice? Or does the very act of participating in this economy perpetuate the inequalities it seeks to dismantle?

ARMY is a global fandom with hundreds of millions upon hundreds of millions of dollars in purchasing power. Our consumption has fed HYBE and emboldened the company to continue platforming Zionists. While this consumption has fed the company, in order to now stop the platforming of Zionists we must deprive the company of what initially allowed it to become emboldened in the first place. This means boycotting, which also means going against what many ARMYs personally value as proof of fanship. It is a direct contradiction that devolves into violence.

ARMY Underground: Weaponizing Fandom Norms

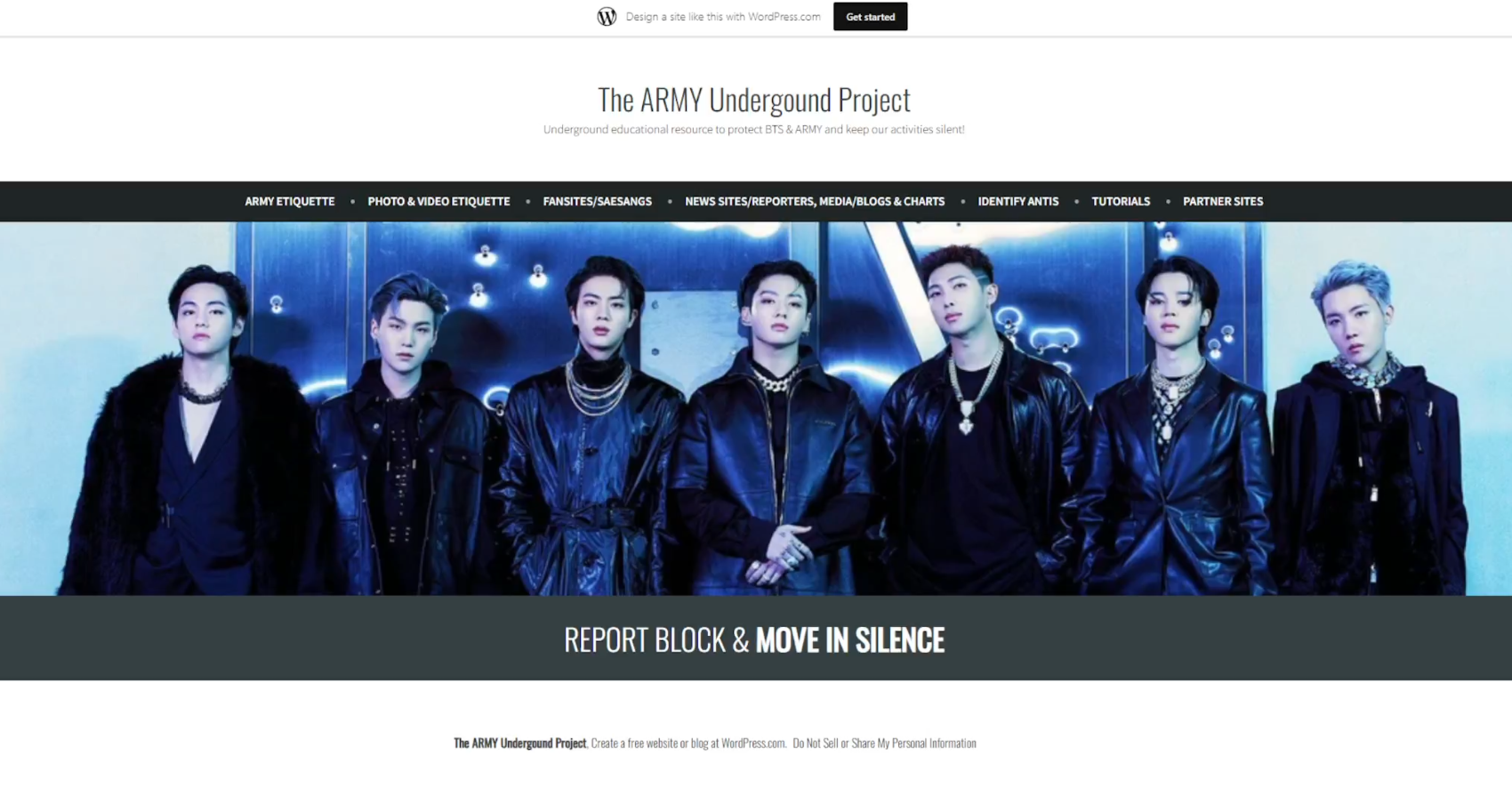

The HYBE boycott didn’t just divide ARMY—it gave rise to some of the fandom’s most hostile dynamics. Among these was the short-lived but highly contentious “ARMY Underground,” a "covert" operation launched to suppress dissent and silence pro-boycott voices. Operating through both a Twitter account and a website, ARMY Underground claimed to protect the fandom’s unity but instead was a potential weapon for policing fandom norms and targeting marginalized voices.

ARMY Underground’s website was a detailed playbook for identifying and punishing perceived “antis.” It featured sections like “Photo & Video Etiquette,” “Fansites/Sasaengs,” and the now-infamous “Identify Antis” page. An anti-fan is someone who actively dislikes a particular person, group, or thing and often expresses this dislike publicly, sometimes by criticizing, mocking, or opposing it. Unlike someone who is merely uninterested, an anti-fan actively engages in negative behavior toward the subject of their dislike[1].

Gray, Jonathan. “New Audiences, New Textualities: Anti-Fans and Non-Fans.” International Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, Mar. 2003, pp. 64–81. SAGE Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877903006001004. ↩︎

While the above definition of an anti-fan is the broad understanding of "anti," fandom communities are constantly in negotiation as to what an anti for their particular fan community might be. Therefore, this ARMY Underground project, can be seen as extension of this negotiation.

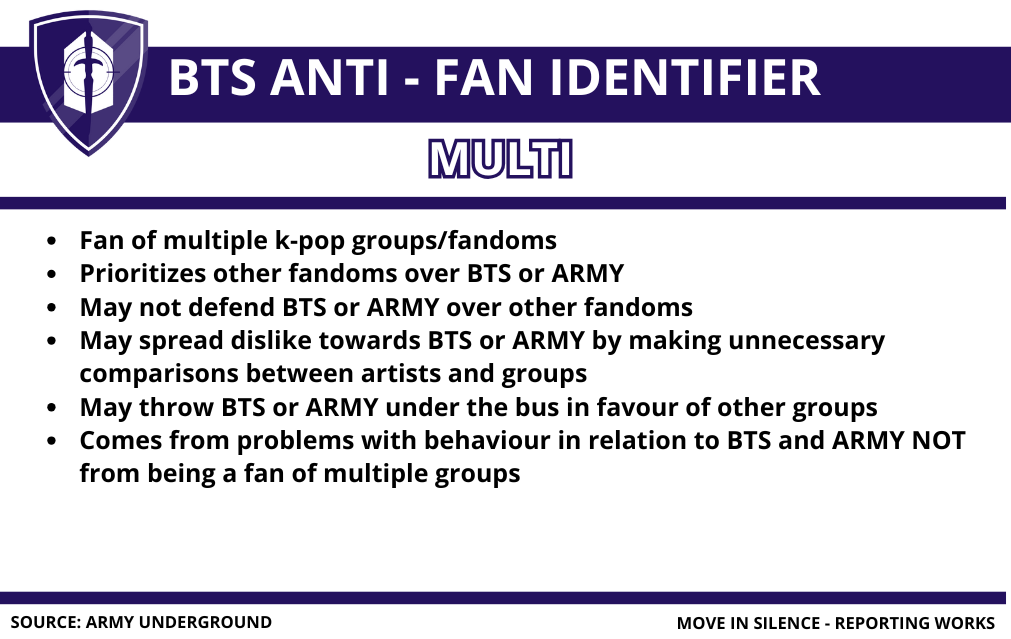

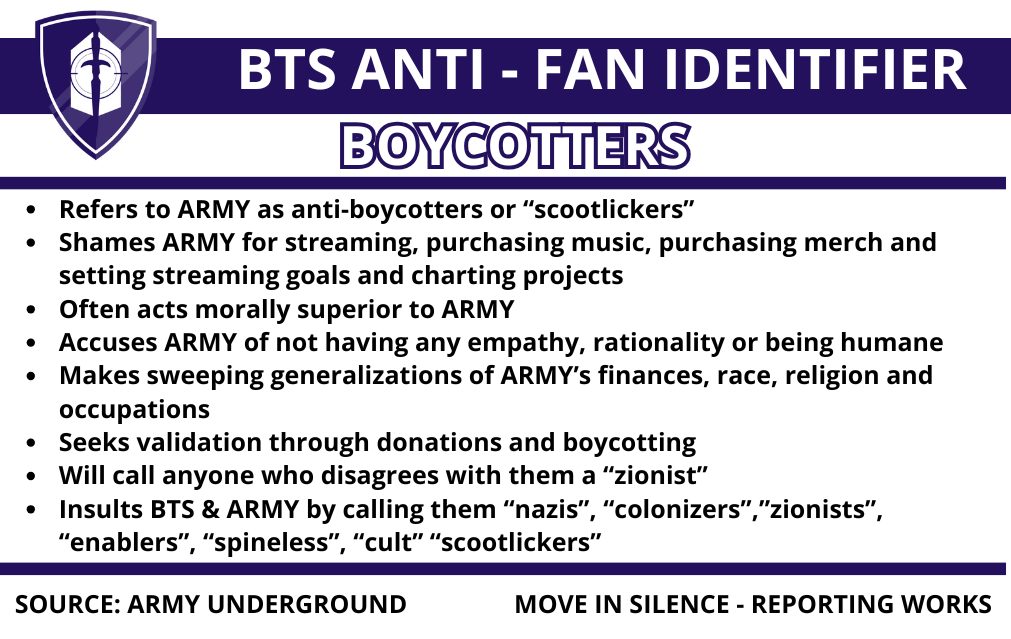

Here are two examples of the "identify anti" images shared on the website:

![BTS anti-fan identifier, diet solos. Spread misinformation about BTS & ARMY. Shares fansite pcitures & defends fansites. Defends solo fanbases. Displays heavy favoritism towards a member. Add to dogpiling on ARMY fanbases. Pushes narratives of mistreatment of BTS members. Actively cancels ARMY accounts and fanbases. Trends problematic hashtags and contributes to solo hashtags, eg. "bts disband", "free jimin", "jungkook deserves better", or "bighit/hybe apologize to [member]" etc. Source: ARMY Underground, Move in silence - reporting works](https://www.kateringland.com/content/images/2025/01/anti-identifier-diet-solos-1.png)

The full list included (in this order):

- Akgaes - "Solos"

- Diet Solos

- Boycotters

- Multi

- Manager Anti - "Mantis"

- Shippers

All of these antis identified on the informational cards are seen as actively harming both BTS and the ARMY community. They not only engage in behavior deemed "inappropriate" by the community (such as sharing fansite[1] photos or spreading misinformation), but also encroaching or attacking ARMY in ARMY spaces.

A fansite is a platform, typically run by a dedicated fan, that shares high-quality photos, videos, and updates about a K-pop idol or group. These fansites are somewhat like the Western notion of the paparazzi, as they often follow idols to public events, airports, and even personal schedules to capture exclusive content. While they are considered integral to the K-pop ecosystem—helping to promote idols and engage fans—they can also be harmful when they invade idols’ privacy, cross boundaries, or exhibit obsessive behavior. In particular, BTS ARMY widely believes that BTS has outgrown fansites, as the group’s global popularity no longer requires such promotional efforts. As a result, fansites are now largely seen as harmful to both BTS and ARMY, with their invasive actions often clashing with the fandom’s values of respect and privacy. See also: Kim, Jungwon. K- Popping: Korean Women, K-Pop, and Fandom. 2017. University of California, Riverside, Ph.D. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2025491109/abstract/50F5037CCF44BC5PQ/1. ↩︎

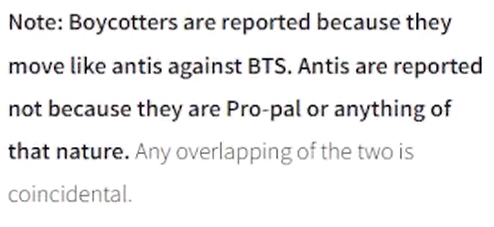

Notably. under the Identify Antis page, the site included a detailed checklist for boycotters, painting them as fandom enemies.

After the website started circulating and gaining criticism on ARMY Twitter, they added the following note under the Boycotter's card:

This rhetoric weaponized the fandom’s values of loyalty and positivity to frame pro-boycott voices as disruptive, even anti-BTS. The group encouraged mass reporting, blocking, and unfollowing campaigns to isolate dissenters[1]. Pro-boycott fans who spoke out faced coordinated harassment, including doxxing, threats of violence, and tanking the reviews of boycott-aligned projects (such as our own podcast). It's worth noting that all of these tactics have been used by ARMY and anti-ARMY groups well before current tensions around the boycott. This current violence and gatekeeping just serves as a clear example of these behaviors.

Who they are reporting to and the significance of blocking we will save for another blog article. ↩︎

ARMY Underground unraveled almost as quickly as it appeared. Within 24 hours of its launch, its admins were exposed, leading to widespread backlash even among anti-boycott fans. One admin publicly posted a string of emotional tweets—“I am not God” and “I am normal”—before ultimately deleting the ARMY Underground account and shutting down the website. The fiasco left behind a glaring question: Why did some think the fandom need ARMY Underground in the first place?

The rise and fall of ARMY Underground reveals the dangers of weaponizing fandom norms. By framing dissent as disloyalty, the initiative suppressed meaningful political dialogue in favor of performative unity. This dynamic disproportionately harmed marginalized fans, particularly Palestinians and pro-Palestinian ARMY, whose calls for justice were met with hostility or outright erasure.

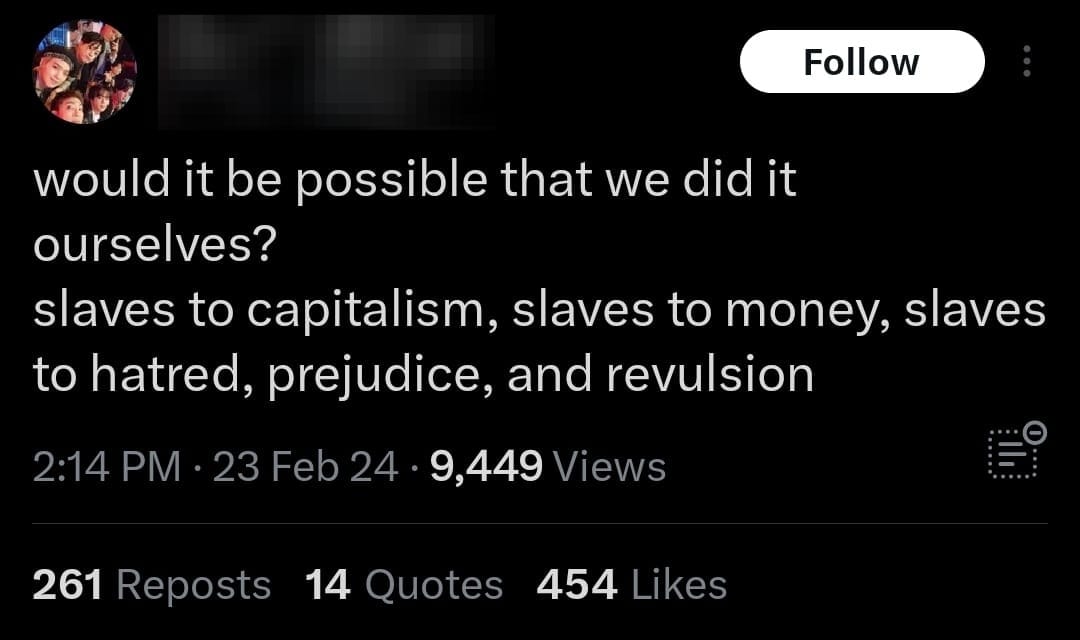

The violence enacted onto Palestinian and pro-Palestinian ARMYs does not only come from non-marginalized voices, but also fellow marginalized voices. This type of cyclical violence from other people of color and gender marginalized individuals is often done in proximity to power. Many of these people falsely believe that by contributing to the oppression of other marginalized people, they will not experience or be harmed by that oppression.

This promise of power if one chooses to contribute to oppression becomes the way people already in power neutralize tangible, radical change. If all marginalized voices decided to mobilize tomorrow and drop any idea of "normalcy" under the current oppressive world we live in, then change could come swiftly. However, people in power whisper promises of power to marginalized individuals, creating divisions to upkeep "normalcy."

This is why we see many supposedly radical activists pop up and quickly become neutralized to continue contributing to oppressive systems. Someone becomes a champion for women's rights and in five years you see them running a yearly "protest" that's really a parade and twelve foot walk. Someone becomes a fiery voice of a generation against gun violence and in five years you see them working under a politician's office. People in power will promise them power in ten, fifteen, maybe twenty years if they just play their cards right and keep their heads down. But the world cannot wait twenty years. Palestine cannot wait twenty years.

Many would find it ridiculous to apply this larger thinking about social movements and activism to BTS ARMY, but the same logic applies. BTS ARMY has created a cycle of violence between marginalized peoples and many think that if they maintain "normalcy" with streaming and monetarily contributing to HYBE's existence that platforms Scooter Braun then everything will go back to "normal."

We can go back to streaming 24, maybe even 48 hours straight? We can go back to buying 100 albums and not blinking at the price tag or environmental impact? We can go back to how everything was before? Yet, we can't because not only have ARMY changed but the world has changed. Many ARMYs refuse to accept that change. Thus, the creation of ARMY Underground and the continuation of violence.

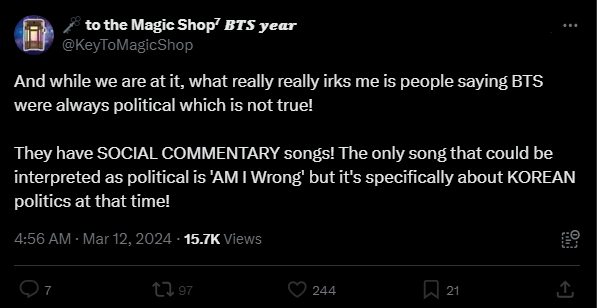

ARMY Underground also exposed the deeper fragility of ARMY’s collective identity. For years, the fandom has celebrated its activism and diversity, yet these values crumbled under the pressure of a moral reckoning. In fact, many ARMYs went to great lengths to show that ARMY has never been about politicization or activism. By prioritizing BTS’s capitalistic success over systemic justice, as we see with this ARMY Underground example, we find a troubling truth: fandom loyalty can often conflict with accountability.

But let’s get one thing straight: “political” doesn’t just mean government elections or politicians arguing on a stage. It’s about power—who has it, who doesn’t, and what we do about that. Enter prefigurative politics: a fancy term for practicing the values you want to see in the world, right now, instead of waiting for some distant utopia. In fandom spaces like ARMY, this could mean building a culture that actively challenges oppression—whether it’s racism, sexism, or exploitation—while embodying the values of care, equity, and accountability. This is what BTS is all about. Namjoon encapsulates this idea, stating in an interview with Variety, "We are not political figures, but as they say, everything is political eventually. Even a pebble can be political."

The HYBE boycott fight shows how easy it is to default to the systems we claim to resist, prioritizing success and image over justice. If fandoms are going to call themselves movements, they can’t just look the part. They have to practice what they preach. They don't get to celebrate their diversity and activism while also oppressing and dismissing the marginalized.

The HYBE boycott and the rise (and fall) of ARMY Underground highlight a recurring pattern within ARMY. The fandom thrives on the idea of shared values, but those values are often narrowly defined and inconsistently applied. Efforts to silence dissent don’t just harm individuals—they erode the very principles of inclusion and justice that ARMY claims to uphold.

Beyond Performative Activism: Reflecting on and Redefining ARMY’s Values

The HYBE boycott is more than a flashpoint in ARMY’s history—it’s a moment of reflection. For years, the fandom has celebrated its ability to mobilize for justice, amplifying marginalized voices and raising funds for global causes. These accomplishments are undeniable, yet they often exist within the boundaries of what feels safe and symbolic. The boycott disrupts these patterns, inviting ARMY to imagine what fandom-based activism could look like if it fully embraced systemic critique and transformative action.

At the heart of this reflection is the question of what it means to be a fan. For much of its history, ARMY has equated devotion with monetary participation: streaming, buying, and endlessly boosting BTS’s success. While this model has propelled BTS to unprecedented global heights, it has also created hierarchies within the fandom, where financial ability often dictates who is seen as a “true” ARMY. This transactional approach to fanship doesn’t just exclude—it contradicts BTS’s ethos of connection and solidarity.

Yet, ARMY is not a monolith. Its vastness is its strength, encompassing a multitude of values and priorities. Some corners of the fandom are deeply rooted in social justice, using collective power to challenge oppression and support marginalized communities. Others prioritize creative expression, fostering vibrant ecosystems of fanart, fanfiction, and collaborative storytelling. These quieter spaces reflect the best of ARMY: a community built on passion, ingenuity, and inclusivity.

At the same time, not everyone in ARMY sees themselves as activists or even wants to be. For many, BTS is simply a source of joy and connection—a fandom hobby that offers an escape from the pressures of everyday life. This, too, is valid and important. The tension doesn’t come from those who just want to fan in peace but from the factions within ARMY that have prescribed rigid definitions of what it means to be a fan. For these groups, being an ARMY is about more than enjoying BTS’s music—it’s about breaking records, boosting stats, and pouring money into the BTS industrial complex. This is where the real conflict lies: between those who see fandom as a personal experience and those who demand labor, money, and loyalty as proof of belonging.

Still, the loudest and most visible parts of the fandom often reflect its fractures. These factions, driven by rigid definitions of loyalty and fanship, can drown out more thoughtful voices. Aggression directed at pro-boycott fans, the prioritization of corporate success over ethical accountability, and the silencing of marginalized perspectives reveal the fault lines within ARMY’s collective identity. These tensions aren’t new, but the boycott makes them impossible to ignore.

One of the fandom’s most significant challenges lies in its tendency to look to BTS as its moral compass. This isn’t inherently negative—BTS’s values have inspired millions—but it creates a dynamic where activism often hinges on the band’s explicit guidance. The 2020 Black Lives Matter donation is a clear example: while the fandom ultimately raised $1 million to match BTS’s contribution, much of ARMY initially hesitated to engage with the movement until BTS made their stance known. This reliance on external validation can limit the fandom’s ability to act independently or engage deeply with complex social issues.

The HYBE boycott underscores the need for ARMY to cultivate a more autonomous moral framework—one that isn’t dependent on BTS’s cues but driven by an intrinsic commitment to justice. With BTS fulfilling their military service, this moment is an opportunity for fans to embrace their own critical consciousness, navigating difficult questions about ethics, accountability, and community without the safety net of the band’s explicit direction.

This reflection also requires confronting the systems fandoms are embedded in. Capitalism thrives on consumption, and K-pop fandoms are uniquely entwined with this cycle. The boycott challenges ARMY to imagine activism that operates outside these constraints: What would it mean to act in solidarity with marginalized communities in ways that resist capitalist exploitation? How can fans use their collective power without feeding the very systems they hope to dismantle?

This isn’t about abandoning ARMY’s identity—it’s about evolving it. The fandom has already shown the power of collective action. Now, it’s a question of focus and intent. By prioritizing inclusion, systemic critique, and shared values over rigid hierarchies or consumerism, ARMY can become more than a fandom. It can become a model for transformative community action, proving that collective identity can be a force for liberation, not exclusion.

Conclusion: A Wake-Up Call and a Call to Action

The HYBE boycott isn’t just about corporate accountability—it’s a wake-up call for ARMY members to reflect on their roles within the fandom and the systems they support. It invites individuals to consider how their love for BTS intersects with the complexities of fandom-based activism and to confront difficult but necessary questions: How do we balance loyalty to the band with a commitment to justice? How can we participate in collective action without reinforcing exclusionary norms? And most critically, how do we begin to dismantle oppressive systems when we’re complicit in upholding them?

This moment reveals a truth often overlooked in fandom spaces: not every fan joins a community with the intent to be an activist, and that’s okay. There is room within ARMY for those who simply want to celebrate BTS’s artistry and enjoy the joy the band brings to their lives. The real tension lies not with these fans but with those who impose rigid definitions of what it means to be an ARMY—equating devotion with labor, money, and loyalty to corporate goals. These factions create fault lines that make it harder to embrace the diversity and individuality that are ARMY’s greatest strengths.

For individuals, the HYBE boycott offers an opportunity to redefine what fandom means to them. By rejecting consumerism as the sole marker of fanship, ARMY members can build a more inclusive and justice-oriented vision of fandom—one that prioritizes creativity, connection, and collaboration over spending power. Moving beyond performative gestures requires cultivating an ethical framework that isn’t dependent on external validation, even from BTS themselves.

But this wake-up call isn’t just for ARMY. Fandoms everywhere are facing similar challenges as they navigate the intersection of identity, activism, and consumerism in an increasingly connected world. What could these communities achieve if they channeled their passion into liberation and equity instead of consumption? How might they redefine loyalty—not as blind support, but as a commitment to shared values and transformative change?

ARMY has long prided itself on being more than just a fandom. This moment is a chance to live up to that promise—not by suppressing disagreement or striving for a false sense of unity, but by embracing the diversity, creativity, and moral courage within its community. By prioritizing justice, inclusion, and accountability over corporate loyalty, ARMY can chart a new path—not only for itself but as an example of how fandoms can be forces for meaningful change.

The future of ARMY isn’t about one voice or one vision. It’s about the collective power of individuals choosing to wake up, reflect, and act. Together, ARMY can prove that even in the face of systemic challenges, fandom-based activism has the potential to change the world. And if not change the world, at least make your own little corner of the universe a better place.

If you enjoyed this post, I’d love for you to share it on social media and invite others to join the conversation. Don’t forget to subscribe to my blog for more reflections, stories, and critical takes delivered straight to your inbox. Let’s build a community where joy and connection thrive!

Member discussion