I wrote this blog post over a year ago and have sat on it since then. Today is the 5th anniversary of my most personally traumatic experience with the US healthcare system — the birth of my oldest child. Because of this anniversary I have chosen today to finally push the button and publish this. There is a lot going on in the world right now, but I am honoring myself by giving myself a little space to tell my own story.

I have found myself at a cross-roads these last few months. Where am I going to be working next? What kind of work do I want to do next? That’s the privilege of being a researcher with a PhD. I find the problems that are interesting to me, seek out funding to solve them, and then spend my energy doing just that. My recent soul-searching has been brought on because I am working on the latest iteration of my job application materials. How do I want to position myself as a job applicant? What facets of my researcher identity are most important to display?

At the same time as this soul-searching, I have been working closely with my dear cousin Annie. We have been gobbling up readings on Indigenous Studies and methods and thinking about a future research agenda that firmly re-centers disenfranchised communities at the heart of the research agenda, instead of privileging Western science and thought.

To this end, I’ve read Indigenous Methodologies by Margaret Kovach (you can read my twitter thread about it here). One of the key things I’ve learned is that personal story and who you are as a researcher are integral to the research process and to the outcomes of the research. As someone trained in Western science, I’ve been taught to obfuscate myself from the research. Clearly delineate where my data and I are in time and space. But that’s not entirely possible. In fact, in recent papers in my field of HCI, I am seeing more and more scholars (usually earlier in their careers) put “positionality” statements. We are here in our research. We chose our field sites and our data collection methods for a reason. If we are solving problems, hopefully, they are things we are passionate about.

Somewhere along the way, my story had been lost. Perhaps not lost, but very carefully hidden — tucked away only to come out in darker moments with close confidants. My friends and family have joked at how good I am at compartmentalizing. Now, at this cross-roads, I feel the need to reconcile these different parts of my life. I need to be more open about who I am, at least in a small way, in order to tell the true story about my research and my career.

I am bipolar. I was diagnosed at 19 years old during my first year of undergraduate. This is not unusual.

I was only diagnosed after a tumultuous few months of beginning college. Moving away from my parents and friends was hard. Having real autonomy over my own schedule was exhilarating, but also hard. I decided to see the school therapist. This is also not unusual for a first year college student.

The first couple of weeks of seeing the therapist were fine. We talked about my dreams and the stress of getting used to college level work. Then things, as they say, went off the rails.

One day I went to the therapist and said, rather off-handedly, I thought, that was feeling kind of low that day. I mean this was the reason I was seeing her in the first place. But instead of sitting down and chatting about it, she marched me down the hallway to the registered psych nurse. In what became a bewildering appointment, where I mentioned at least once a family history of bipolar (something I had suspected in myself since I was sixteen), I walked out with a bottle full of antidepressants. Turns out this was not a great move on the nurse’s part, but also the quickest way for me to prove my theory about being bipolar [this is sarcasm, I did not take the pills simply to test my mental health].

This was not the first time I had been discounted in my own health care. Women experience this all the time. However, this marked the moment in my life when I went from being mildly annoyed at being ignored by clinicians to experiencing true violence and oppression by the system. And this has followed me ever since.

It took months to get a diagnosis after that incident and was only made possible by my wonderful mother who knew who how to navigate the medical system. It took me additional years to really “recover” from the trauma of that first year of college. There were periods of trying different medications and therapy. Despite my initial engagements with mental health care, I did go back (to other clinics, more carefully researched). But there were lots of ups and downs trying to learn triggers, figure out what was going to work for me and what didn’t, and finding a new normality. Getting through this period of my life did not happen without the constant support of my family, my partner, and close friends. I would argue that I will never fully recover and that the emotional scars from that experience shape everything I do even today.

One real tangible way this has impacted me was my continual marginalization in my own healthcare. As soon as the official diagnosis was in my medical charts, I was no longer a reliable or trustworthy patient. I had “severe mental illness” after all. I was denied pain medication after a root canal. I was ignored by doctors and nurses and almost died during childbirth in what was otherwise a normal pregnancy. Let me say it again: I very nearly died. If it wasn’t for a kind night shift nurse two days after my c-section, I wouldn’t even have been told. I wouldn’t have been given the information needed when planning the delivery of my second child (at a completely different hospital in a different state).

This ripple effect just keeps going. My grades in undergrad were understandably horrendous. I had plenty of teachers and fellow students who didn’t believe in me and told me so. Having my ability and trustworthiness questioned repeatedly has taken its toll. This is, I imagine, what imposter syndome on steroids might look like. Some days I question if what I am experiencing and feeling is real or not — luckily, these days have become fewer and far between in recent years. However, those early days of mistrusting myself and hearing that mistrust echoed all around me still haunt every decision I make, especially the big life decisions.

My anger and pain became fuel. I wanted to do the work to help other people experiencing disenfranchisement. I have had wonderful mentors who supported me as I aspired for a PhD and a wonderful advisor who took a chance on me. I successfully completed a PhD in Informatics within the normative time frame (5 years) while being bipolar and while having two children (and almost dying).

I carefully toed the line in my research. Always studying disability, but never bipolar. Careful to help brethren close to me, but never to reopen those wounds hiding just below the surface. I discovered disability studies and social justice. Suddenly, the world was a better place because there were answers beyond subjugation in a medical context. I could push the boundaries of my own field by showing how oppression is happening right here in our own backyards.

Then I began a postdoc in digital mental health. I told myself I could handle it. It would hit close to home, but that it was going on 15 years since The Incident and my subsequent diagnosis. Unfortunately, I found the experience harder than I ever imagined. All of the sudden there are daily reminders of the “severe” nature of bipolar (because we focus on depression and anxiety). There are small cuts that bring back ghosts of oppression and violence. I lived in fear of “coming out” and the implications of what that means in a space that specifically studies mental illness. And I worried how this will impact my steps forward. How does this change my career trajectory? Can I still do the work I want to do and help the communities who need my help the most?

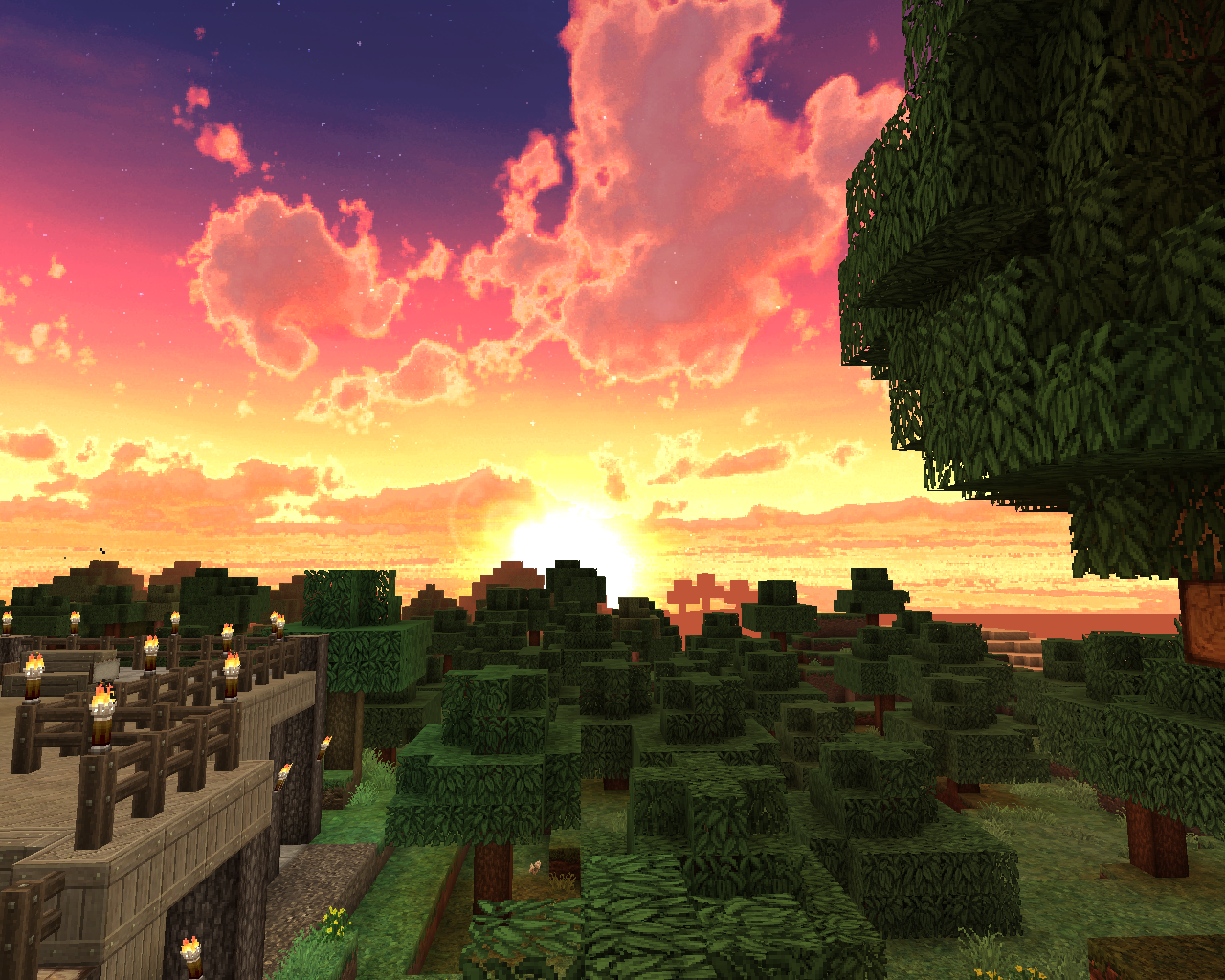

Those cuts remind me why I began this journey in the first place. I want to go to people where they are and help them. Whether that’s giving them access to healthcare or giving them a safe space that isn’t the institution that is our healthcare system. I want to bring back joy through sociality and play.

Beyond my own body of research, I want to be a mentor to others coming after me facing challenging barriers to their work. My advisor took a chance on me and I want to be able to pay that forward with future generations of students.

I’ll leave you with words 18 year-old me wrote, that, in some ways, are still hauntingly true today:

I am the shadow on the wall in your mind

I am the one gallantly dancing across the brick

But the shadow you see, it can’t possibly be all of me

I have faded into nothing

Becoming the invisible, the ignored, and the tormented

I am the shadow

On the wall In your mind.