Preview: For members of the Autcraft community, they are not only coming to terms with their identity as autistic individuals, but they are also playing with and practicing other identity roles. In this article, I briefly discuss the impact of the “gamer” identity. I also explore some possible implications for researchers who are interested in—or concerned about—games.

Disability and Play

Throughout history, disability has been a part of interactions and relationships in society as a way of creating the category of “other” and, therefore, ensuring the dominance of the category of “normal.” As an aspect of their life, a person’s disability seems all encompassing. This leaves little room for any other aspects of their identity or life. Not only is the person then defined by their inability to interact or engage in the world, but they are then not seen as having ability in anything. This includes those who play games. People with disabilities are seen as not able to play—or maybe not even interested in playing.

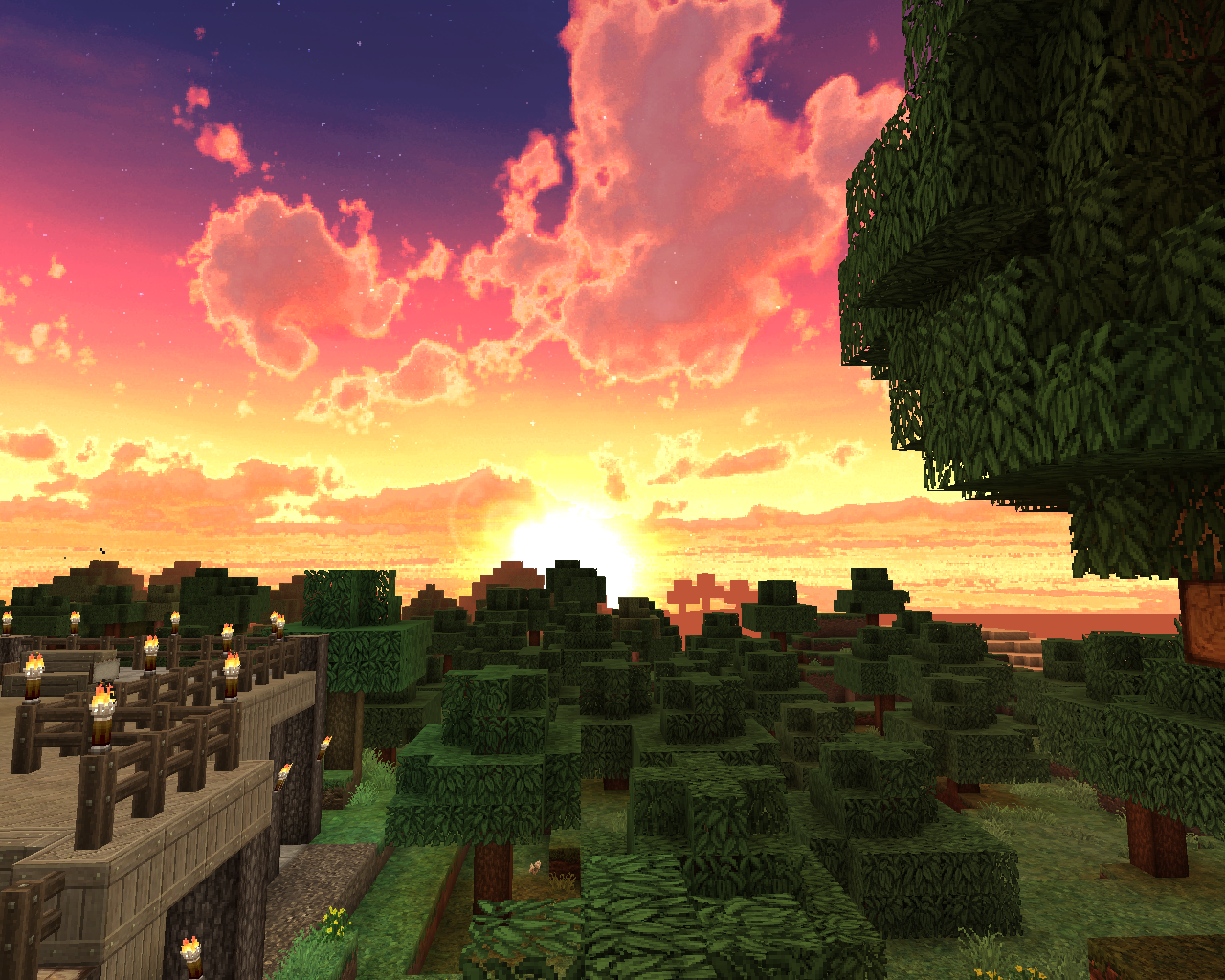

In this work I continue to analyze data from my virtual ethnography of the Autcraft community—a community for autistic kids who play Minecraft. You can read more about it here.

Background: Problematic Video Games?

There are a lot of concerns about video games, especially when it comes to children playing them. These concerns range from misbehavior, addiction, and bullying. This is especially true for autistic children. Many researchers have gone to great lengths to show the negative aspects of games for autistic people.

However, while many people don’t realize it, a lot of what is happening in these video games is a very social experience. As I have shown in my other work, the community members of Autcraft are playing with each other, making friends, and gaining confidence in their own social abilities.

Finding Identity

In this paper, I show how not only are the autistic community members of Autcraft embracing their identities as autistic people, they are also embracing and practicing the identity of “gamer.” They post to the forums about games, apply to be YouTube content creators, and embrace other aspects of nerdy game culture.

While they are trying on these different roles, this is complicated not only by their autism, but also by exploration of gender identity, among other roles. This is especially important given how hostile some gaming environments can be for those who are straight men. By focusing on one identity, it’s easy to lose sight of these other emerging aspects of the community members’ lives.

Implications for Research

There are two implications for research from this work.

- Promoting pro-social gaming. There has been a drive to understand the negative aspects of gaming, however less has been explored in the positive. Especially for individuals with disability or difficulty accessing other forms of sociality and play, games can be a great resource.

- Need for broader understanding of individual players. There is a need to look at players through an intersectional lens. Players are not only gamers (or not, depending whether they adopt this label or not), but also have varying ability and disability, gender identities and expressions, cultural and racial identities, and so on. By narrowing the scope too much, we sometimes will miss the important intersections of these identities and their impact on the person’s access to play (and social interactions).

For more details about our methods and findings, please see my paper that has been accepted to FDG 2019 (to appear in August 2019). Full citation and link to the pdf below:

Kathryn E. Ringland. 2019. “Do you work for Aperture Science?”: Researching and Finding the Gamer Identity in a Minecraft Community for Autistic Children. In FDG 2019. [PDF]

Acknowledgements: I thank the members of Autcraft for the warm welcome to their community. Thank you to Chris Wolf, Amanda Cullen, Severn Ringland, Kyle Lee, and the anonymous reviewers for their feedback on various iterations of this work. Special thanks to: Gillian Hayes, Tom Boellstorff, Mimi Ito, and Aaron Trammell. Thank you to Robert and Barbara Kleist for their support, as well as the ARCS Foundation. This work is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH115882). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This work is covered by human subjects protocol #2014-1079 at the University of California, Irvine.

0 Comments

1 Pingback